Much of the UK debate surrounding Brexit has revolved around two kinds of border. The first is the land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. We have seen a combination of economic concerns about the free flow of people and goods and security concerns about the border becoming re-militarised.

Much ink has also been spilled on the maritime border between England and continental Europe. Ongoing challenges with so-called “illegal” migration from the continent, and Kent’s potential role as a “lorry park” in waiting – particularly in the case of a no-deal Brexit – illustrate the significance of the English Channel both as an actual and a symbolic border.

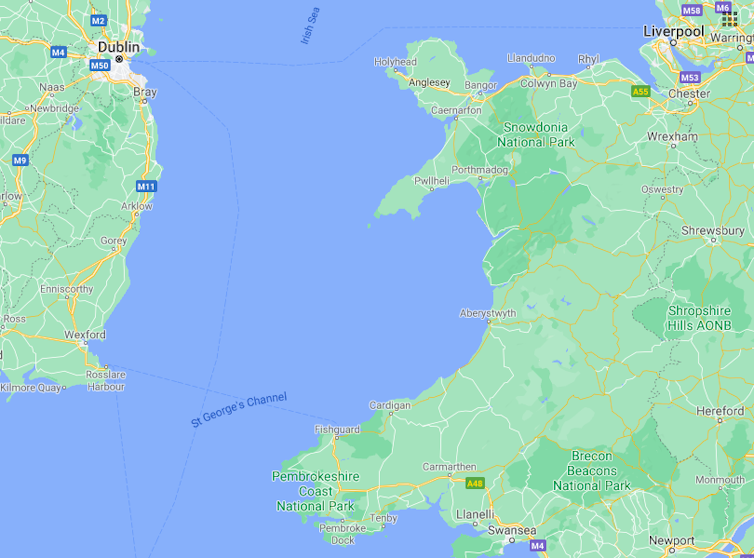

Yet the Irish Sea, and by extension the maritime borders between Britain and Ireland, needs to receive more focus. The UK’s Internal Market Bill, which aims to counter any potential economic and political divergence between Northern Ireland and the British mainland, could significantly affect UK ports like Liverpool, Holyhead, Fishguard, Pembroke Dock and Milford Haven, and the Irish ports of Dublin and Rosslare.

We are exploring the historic and contemporary connections between Holyhead, Fishguard, Pembroke Dock, Dublin and Rosslare as part of the Ports, Past and Present project, which is funded by the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation Programme. These port communities and the routes that connect them have long been of critical political, economic and cultural importance to both countries.

They are facing a number of profound and even unprecedented challenges as the transition period draws to an end. Our work to date has shown that efforts to get to grips with these challenges have been more far-reaching and sustained in the Republic of Ireland than in Wales.

The land bridge

The first concern is with the amount of infrastructure put in place to deal with the additional border bureaucracy required following Brexit. Ireland has made a considerable investment into new customs infrastructure. For instance, Dublin Port has invested some €30 million (£27 million) and re-purposed 10 hectares of land, including building new customs posts and associated facilities. Similar developments have been conspicuous by their absence in the Welsh ports facing the Irish Sea.

This may partly reflect a lack of political will, but there are also fundamental practical issues making it harder for Welsh ports to become Brexit-proof. For instance, the approach to the port and ferry terminal at Pembroke dock passes through the centre of Pembroke town along single-carriage roads, which makes it a challenge to build new border infrastructure.

With space at a premium, no firm decisions have yet been made about what land might be redesignated for facilitating the new customs procedures which will be required after Brexit. Similarly, Holyhead, the second busiest port in the UK, has little space to invest in infrastructure either.

Another issue is that key supply chains facilitated by Welsh and Irish ports are liable to be undermined by Brexit. To take just one example, ready-made sandwiches sold in Marks and Spencer on Dublin’s Grafton Street are produced in the UK before being exported every morning via Holyhead to Dublin, in time to service lunchtime demand. To what extent such vital trade links will remain viable is an open question, and relies on what sort of deal (if any) is eventually concluded between the UK and EU.

A port like Holyhead is also an important link in the so-called British “land-bridge” that connects Ireland with mainland Europe. In 2018, around 40% of total Irish trade was facilitated through this link, which equates to around 150,000 lorries crossing to the European mainland via UK ports.

At present, hauliers can transport Irish goods to mainland Europe along this route in less than 20 hours, but this is likely to be slowed down by the UK’s exit from the EU customs union. Not surprisingly, Dublin and Rosslare are developing new direct ferry routes to continental Europe that would remove the need for this land bridge.

Shared heritage

Our project has also identified the pressing need to consider the far-reaching cultural consequences of Brexit on these ports and their surrounding communities. Throughout history, Holyhead, Dublin, Rosslare, Fishguard and Pembroke Dock have been staging posts in the journeys of merchants, administrators, soldiers and revolutionaries, as well as poets, authors, scientists and tourists.

The UK ports welcomed generations of Irish immigrants coming to work in different industries, not least construction and railways. The history of these ports is the history of the shared and conflicted connections between Ireland and the UK.

The port communities reflect this rich heritage. Street, place and family names testify to the longstanding connections between Ireland and Great Britain. Many people living and working in these towns are a product of this shared ancestry.

The community groups that Ports, Past and Present is working with on both sides of the maritime border are keen to maintain cultural links, but Brexit could make this more difficult. There are questions, for example, about what type of financial support might be available to cross-border initiatives after Brexit, once current EU-funded programmes have run their course. New divisions - both material and symbolic - between Wales and Ireland after Brexit will be to the detriment both of the port communities and the countries overall.

Taken together, it shows why this “forgotten” border needs to be taken seriously. The UK must grapple with a series of practical challenges along its Irish-facing ports if we are to make Brexit work economically and politically. But there is also an urgent need to reflect on the cultural significance of this separation and find ways to manage its fallout.

Jonathan Evershed receives funding from the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation Programme as part of the Ports, Past and Present project team. He has also received funding from the ESRC and AHRC.

Jonathan Evershed receives funding from the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation Programme as part of the Ports, Past and Present project team. He has also received funding from the ESRC and AHRC.

Rhys Jones receives funding from the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation Programme as part of the Ports, Past and Present project team. He has also received funding from the ESRC, AHRC, Horizon2020, Leverhulme Trust and the Welsh government.

Jonathan Evershed, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of English, University College Cork

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off

Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off  Bank of Japan Signals Readiness for Near-Term Rate Hike as Inflation Nears Target

Bank of Japan Signals Readiness for Near-Term Rate Hike as Inflation Nears Target  U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains

U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient

Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient  Russian Stocks End Mixed as MOEX Index Closes Flat Amid Commodity Strength

Russian Stocks End Mixed as MOEX Index Closes Flat Amid Commodity Strength  Global Markets Slide as AI, Crypto, and Precious Metals Face Heightened Volatility

Global Markets Slide as AI, Crypto, and Precious Metals Face Heightened Volatility  RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal

RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal  Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure

Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure  Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns

Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns  India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out

India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out  U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock

U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock  Thailand Inflation Remains Negative for 10th Straight Month in January

Thailand Inflation Remains Negative for 10th Straight Month in January  China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices

China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices  Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility

Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility  South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks

South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks