When Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin met in Geneva in June, many expected the new US president to restart a serious dialogue with Moscow and end the downward spiral of the US-Russia relationship. Tensions between the two states have been rising since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the erratic policy of Donald Trump only added to the catalogue of contentious issues.

But anyone hoping the climate emergency would be front and centre of bilateral discussions – especially after pledges to cooperate on the issue in April – was deeply disappointed. Putin and Biden decided to ignore the biggest current global challenge – and one which has some chance for Russian-US cooperation. Instead, they focused on the areas where the prospects for cooperation remain bleak: cybersecurity and arms control.

The conspicuous absence of climate change on their agenda is concerning. Neither US climate czar, John Kerry, nor his Russian counterpart, Ruslan Edelgeriyev, took part in the Geneva talks. When Putin was asked in a press conference whether he discussed the climate emergency with the US president, he simply ignored the question.

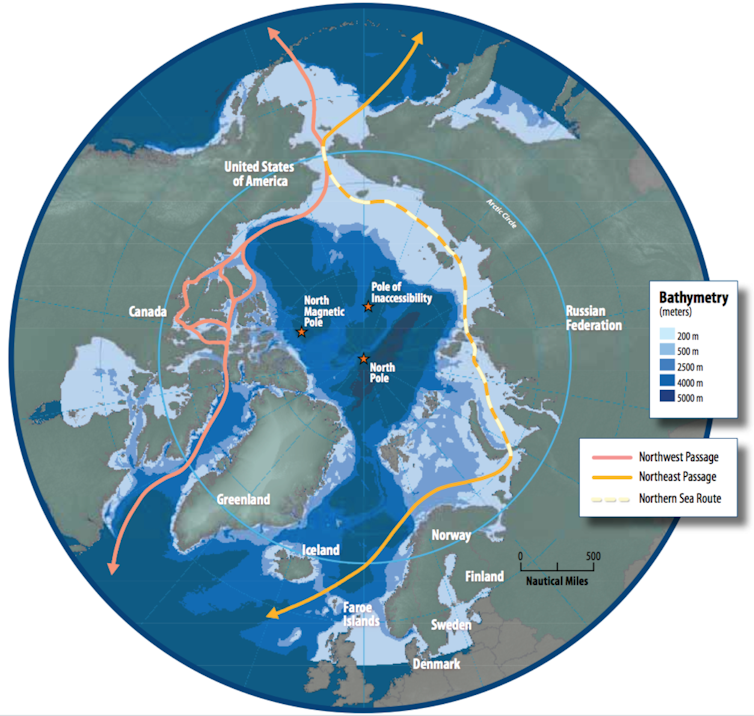

He did mention global warming when he spoke about the Arctic. Refuting US accusations of militarising the region, Putin sketched a vision of prosperity along the Northern Sea Route – a maritime passage between Asia and Europe – once the melting ice enables navigation all year round.

The irony that this sea passage will become navigable as a result of rising temperatures seemed lost on Putin who concentrated instead on the benefits rather than challenges of global warming. What was even more surprising, President Biden was not even asked about climate change, nor chose to bring it up during his own press conference.

Global warming means the Northern Sea Route will become accessible as the ice melts. Susie Harder/Wikipedia

Trust and cooperation

This strange omission can be explained. Security is the go-to subject when the US and Russia meet. It overshadows all other issues, even if, in the long run, climate change will have security-related consequences. At present, it could reconcile competing interests, as both states would benefit from the development of green technologies and diversifying away from fossil fuel industries. In the meantime, the prospects for cooperation in the security realm look dim.

We still know little about the new “cyber arrangement” the two presidents agreed on, but it can be assumed that an important step towards cooperation has been made. But cooperation requires trust, and – especially with respect to cybersecurity – it requires complete control of domestic hackers involved in cyber-attacks. Both are lacking; trust between the White House and the Kremlin is at its lowest since the cold war.

In terms of control over hackers, Russia is a far less centralised regime than many may imagine, and its institutions are relatively weak. This allows for a number of individuals and groups to engage in activities that the Kremlin prefers to deny any knowledge of.

The 16 areas indicated by Biden, such as energy, transport and financial services, may show clear red lines, but they may also invite malign Russian actors to test the US resolve to respond.

Russia and the US have attempted to establish constructive relations in the cyber-sphere before. There once existed a cyber-group within the Russia-US presidential commission during the Obama presidency, but it met only once. A similar commission was discussed during the first Putin-Trump summit. In both cases, Russia and the US failed to build meaningful and lasting cooperation.

The road to nowhere

When the Russia-US relations hit rock bottom, arms control becomes the one topic pundits expect both sides to discuss. As the two biggest nuclear powers on the planet, Moscow and Washington clearly share responsibility.

But it is an illusion that a strategic arms control agenda will take their bilateral relationship forward. Russia and the US have been unable to reconcile their differences on strategic arms control for almost two decades. Missile defence – which the US has been developing and which Russia cannot afford – remains the bone of contention.

Washington has never been ready to make genuine concessions in this regard. Thus, the adoption of a very brief and vague “joint statement on strategic stability” may turn out to be the only outcome of the arms control dialogue for years to come.

All this leads us to reconsider Biden’s aims for the summit. The meeting was organised at the suggestion of the Americans. It looks like the new US president wanted to tick the Russia box and move on to the real competitor: China.

It looks like Biden deliberately decided not to open any new avenues, even as critically important as climate change. This may be because the White House senses trouble ahead; both states are top world polluters and while they should clearly be discussing ways forward, both have strong opposing constituencies at home.

Instead, Biden chose the status quo of security-related matters and inaction in matters of climate. John Kerry’s recent visit to Moscow may be a harbinger of things to come. It was disappointingly low key, and the US climate envoy did not meet with Putin, speaking to him only by phone. This does not bode well for making climate change a priority in bilateral relations.

Difficult ethical choices lie ahead and, given the urgency of the climate crisis, will need to be taken quickly. Without bold and ambitious joint projects, climate change will remain a footnote to the security-dominated agenda of Russia-US relations. The pragmatism necessary to start effective cooperation on climate change may require loosening of the sanctions against Russia and a closer dialogue with a government that quashes political opposition with more and more resolve.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Marcin Kaczmarski, Lecturer in Security Studies, University of Glasgow

Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales

Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales  Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape

Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape  Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy

Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans

TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans  New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients  South Korea Assures U.S. on Trade Deal Commitments Amid Tariff Concerns

South Korea Assures U.S. on Trade Deal Commitments Amid Tariff Concerns  Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall

Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall  Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify

Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify  Nighttime Shelling Causes Serious Damage in Russia’s Belgorod Region Near Ukraine Border

Nighttime Shelling Causes Serious Damage in Russia’s Belgorod Region Near Ukraine Border  Trump Allegedly Sought Airport, Penn Station Renaming in Exchange for Hudson River Tunnel Funding

Trump Allegedly Sought Airport, Penn Station Renaming in Exchange for Hudson River Tunnel Funding  Iran–U.S. Nuclear Talks in Oman Face Major Hurdles Amid Rising Regional Tensions

Iran–U.S. Nuclear Talks in Oman Face Major Hurdles Amid Rising Regional Tensions  US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks

US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks  China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit

China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit