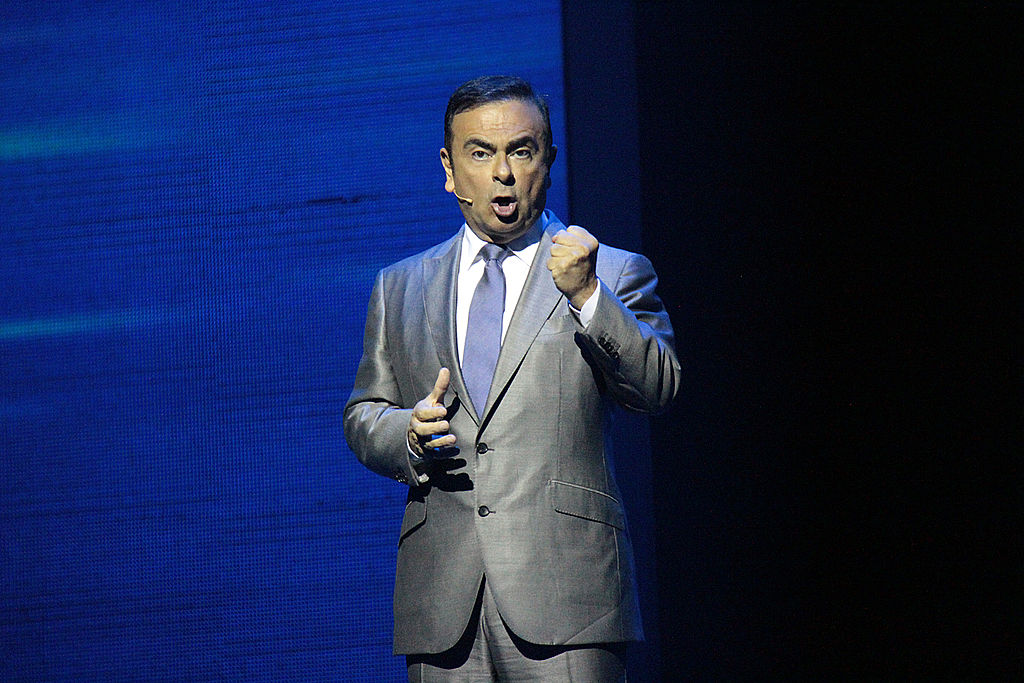

When Carlos Ghosn, the former chief executive of Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, fled from Japan to Lebanon in December 2019 protesting his innocence against charges of financial improprieties, he said his escape was prompted by mistrust of the Japanese criminal justice system.

In interviews from Beirut, Ghosn said he fled bail and escaped the country in order to avoid “injustice and political persecution”. It’s an accusation that the Japanese justice minister, Maskao Mori, flatly refuted.

Over the past year or so, along with colleagues both from Japan and the UK, I’ve been conducting research on the way vulnerable people are treated in both countries’ justice systems. Ghosn’s doubts about whether he would get a fair trial in Japan prompted me to consider whether his claims are justified.

Lay-judge system

At the turn of the 21st century, in an attempt to overcome the Japanese public’s apathy towards criminal justice (though deference to those who dispense it), the government decided to ensure greater citizen involvement in decision-making in trials. Previously, court cases had been exclusively decided by professionals such as judges. Such moves towards public participation are similar to those of many other countries, where, for example, citizens are randomly selected to sit as jurors.

What’s unique in Japan’s lay-judge system, or saiban-in seido, which was introduced in 2009, is that in serious case trials six citizens preside, when requested, over cases in cohort alongside three professional judges. This is the kind of trial Ghosn would likely have faced.

While recent evaluations have found that the Japanese public approve of the lay-judge system, people often either decline (or fail) to attend as saiban-in when called. One reason for this may lie in Japan’s meticulous approach to criminal justice, which means that trials are often long, and people may be unwilling to make such time commitments.

Those willing to undertake their public duty are subject to a preliminary examination of their appropriateness to sit as lay-judges. Decisions to reject may be on reasonable grounds, for example if a candidate is currently undergoing a criminal investigation themselves. However, exclusions may also be at judicial discretion, for which no further reason is required.

Taken together, questions remain over how representative the saiban-in system actually is. Indifferent citizens are unlikely to attend, while those more strident in their views on justice may be over-represented among those who do. Certainly, sentencing has generally become more severe since 2009.

The new approach has coincided with a new requirement for public prosecutors to disclose much more detail of evidence to the defendant and their counsel ahead of a trial. While this makes the criminal justice process more transparent, evidence collected that doesn’t support the prosecution’s case can still remain undisclosed.

High conviction rates

Another issue Ghosn pointed to repeatedly in comments after his escape was the very high rate of conviction for those on trial of between 97%-99%. In the UK, the rate is consistently around 85%-87%. But such comparisons must be treated with caution. In Japan, even those who plead guilty face trial, with such a plea merely forming part of the evidence. The high rates are also attributed to prosecutors being quite risk averse and only proceeding with cases very likely to get a conviction.

Other reasons given for the high conviction rate concern the style of criminal investigations, particularly the focus by Japanese police officers on confession. Suspects can be held without charge or access to counsel for up to 23 days. Studies conducted by Japanese academics have found confession rates of around 65% in serious cases in Japan – markedly higher than those found from research undertaken in England and Wales, where the rate is believed around 40%.

What happens in interviews

Interrogations in Japan serve a number of purposes. Police are meant to gather information and evidence from suspects about the crime and any association with other offences or offenders. But they are also meant to understand the motivation and explanation why the criminal act was committed, and to encourage suspects who admit their offences to show remorse and efforts to reform their criminal behaviour.

Previous work my colleagues and I have conducted on police interviews with suspects around the world revealed that there was an emphasis in Japan on fact-finding about the case, but less effort towards any of the other goals. This is despite beliefs held by police officers that they do conduct interviews to cover all these aims.

In our ongoing research we’ve been talking to Japanese public prosecutors who also undertake pre-trial interviews with suspects who have confessed to the police. The prosecutors are telling us they use these interviews to both get the suspect to show remorse and establish reasons for their committing the crime, later presenting these details in court.

Exactly what the police do when interrogating suspects might soon become more clear. In 2019, the law changed to require the entirety of pre-trial interrogations with suspects to be audio or video recorded. Elsewhere, such developments have been argued to lead to improvements in the interrogation process.

In short, Ghosn’s vocal concerns about the rigged nature of the Japanese justice system against the accused may have had greater substance a decade ago. The recent changes are intended to create a more transparent, fair and accountable system. Nevertheless, there remains further areas that need urgent improvement in the pre-trial process. These include a lack of access to legal advice for suspects, long periods of incarceration before charge and a focus towards gaining confessions, rather than a reliable account.

Like all criminal justice systems in the world, the Japanese system is not infallible. However, to suggest that it is fundamentally corrupt appears unjustified.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns

Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns  Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding

Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding  Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive

Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive  Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit

Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit