An international team of researchers, led by Dr Ozren Bogdanovic and Professor Ryan Lister from the University of Western Australia, have found the genetic “switch” that causes one species of animal to look similar to another.

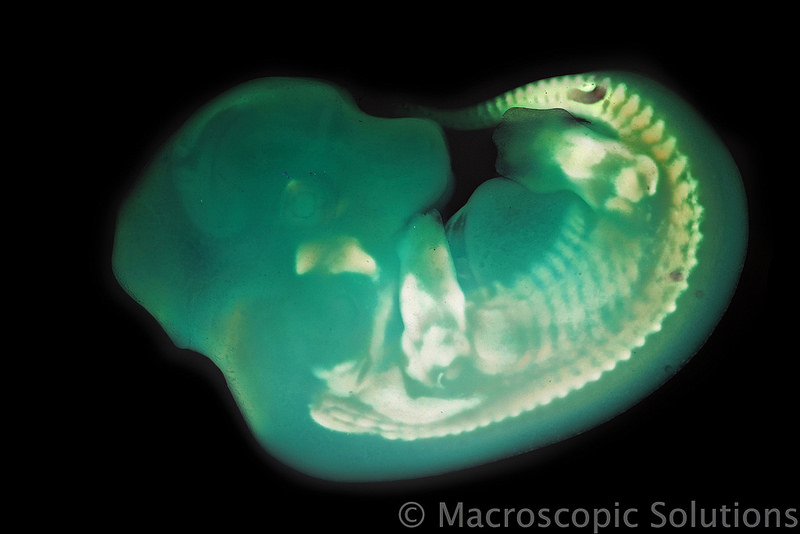

Mice, fish, frogs and even humans look remarkably similar at early embryonic stages, and appear to share the same molecular instructions that are crucial to normal embryo development.

The study, published in Nature Genetics answers one of the fundamental questions in what controls embryo formation. It also provides insights into the mechanisms that could be linked to developmental disorders or cancers.

Signposts that determine the fate of cells

There is a point during early embryonic development, called the “phylotypic stage”, when all animals with backbone, also known as vertebrates, resemble one another. At this stage, a chicken embryo looks almost indistinguishable from a rabbit or a human at a similar stage.

The time it takes to reach the phylotypic stage varies between species. In humans it takes around four weeks after fertilisation, compared to one to two days in fish and toads, to nearly ten days in mice.

However the process that determines how the embryo reaches this stage was unknown.

The phylotypic stage is crucial as it is the period where the template of the body is being laid down. What genes contribute to this crucial period, and how they are turned on in sync, has been a big question.

The researchers found that specific biochemical signals, known as epigenetic changes, decided the fate of the cells in the early embryo. One particular epigenetic mechanism was DNA methylation, which is able to modify DNA molecules and effectively switch off certain genes during embryo development.

The removal of this epigenetic mark would trigger activity of a whole battery of genes that accomplish these first, highly conserved, developmental stages.

“Our findings answer one of the questions about early development, such as the molecular mechanisms that make a ‘heart’ a ‘heart’ and or a ‘limb’ a ‘limb’”, said Dr Ozren Bogdanovic, lead author from the ARC Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology.

In addition, one protein, TET, which in mammals is activated right after fertilisation, was detected the protein in fish and frogs as well during the phylotypic stage.

This means species that were distantly related on the evolutionary scale, even after millions of years, all had the same molecular basis that defined the blueprint of body formation.

A longstanding puzzle solved

Jenny Graves, professor of genetics at La Trobe University, who was not involved in the study, is also one of the first researchers to demonstrate DNA methylation. She said that these findings had significant implications across the field of molecular genetics.

“It’s very significant indeed. It’s a huge paper with an enormous amount of work,” she said. “I’ve always thought that DNA methylation probably had a big role in development, so I’m jumping for joy.”

The study has helped solve a longstanding puzzle on early embryo development.

“There were all kinds of theories going way way back,” she said, stressing the growing impact of epigenetics, the study of the epigenome.

“Every change during development is probably modulated by the epigenome that determines the basic embryonic patterning of vertebrates, and probably also turns on later genes that specify differences between a frog, or a fish or mouse.”

Graves said a next step will be searching for even more conserved patterns across all species. “Some of the most fundamental controls of the way genes work would probably be the same in a plant, or a fruit fly or a mouse.”

It is also certain that humans share the same pathway in embryo development as other species. This common pattern would mean that prior to birth, there is a point where we are virtually indistinguishable in appearance to other species.

“It would be really extraordinary if it weren’t,” said Graves. “It is probably going to turn out that all mammals share these very fundamental patterns and it would be amazing if humans were any different.”

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Novo Nordisk Warns of Profit Decline as Wegovy Faces U.S. Price Pressure and Rising Competition

Novo Nordisk Warns of Profit Decline as Wegovy Faces U.S. Price Pressure and Rising Competition  Viking Therapeutics Sees Growing Strategic Interest in $150 Billion Weight-Loss Drug Market

Viking Therapeutics Sees Growing Strategic Interest in $150 Billion Weight-Loss Drug Market  Federal Appeals Court Blocks Trump-Era Hospital Drug Rebate Plan

Federal Appeals Court Blocks Trump-Era Hospital Drug Rebate Plan  TrumpRx.gov Highlights GLP-1 Drug Discounts but Offers Limited Savings for Most Americans

TrumpRx.gov Highlights GLP-1 Drug Discounts but Offers Limited Savings for Most Americans  Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk Battle for India’s Fast-Growing Obesity Drug Market

Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk Battle for India’s Fast-Growing Obesity Drug Market  Sanofi’s Efdoralprin Alfa Gains EMA Orphan Status for Rare Lung Disease

Sanofi’s Efdoralprin Alfa Gains EMA Orphan Status for Rare Lung Disease  California Jury Awards $40 Million in Johnson & Johnson Talc Cancer Lawsuit

California Jury Awards $40 Million in Johnson & Johnson Talc Cancer Lawsuit  FDA Approves Mitapivat for Anemia in Thalassemia Patients

FDA Approves Mitapivat for Anemia in Thalassemia Patients  U.S. Vaccine Policy Shifts Under RFK Jr. Create Uncertainty for Pharma and Investors

U.S. Vaccine Policy Shifts Under RFK Jr. Create Uncertainty for Pharma and Investors  Merck Raises Growth Outlook, Targets $70 Billion Revenue From New Drugs by Mid-2030s

Merck Raises Growth Outlook, Targets $70 Billion Revenue From New Drugs by Mid-2030s