For the first time, street dancers from 15 countries, in addition to one woman from the Refugee Olympic Team, will be competing for gold, silver and bronze, as breaking makes its debut at the 2024 Paris Olympics.

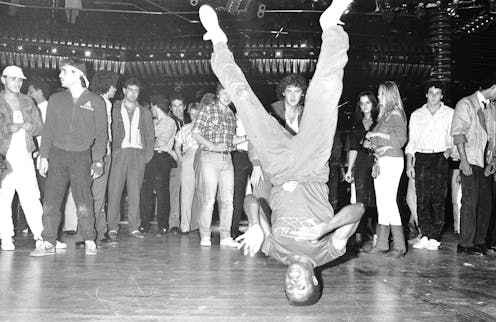

The sport has come a long way from its origins in the Bronx. But the body-contorting, mind-boggling moves that once could be seen only at playgrounds and block parties will now dazzle billions of viewers around the world.

If you’re watching breaking for the first time, you might find yourself stunned that humans can even perform these moves without getting hurt.

As a former dancer, current performing arts physical therapist and biomechanics researcher, I study how dancers twist and bend their bodies in unexpected ways. I train them so that they can safely perform, even as they push their bodies to extremes.

Breakdancers – also known as B-boys, B-girls or breakers – don’t just need to concoct creative moves. They have to develop incredible strength and body control to pull them off – perhaps none more daunting than the headspin.

Nothing routine about breaking

Breaking is a form of street dance that developed in the 1960s and 1970s, drawing from hip-hop, martial arts and gymnastics.

At the Olympics, two athletes at a time will compete in improvised battles, in which competitors take turns trying to one-up each other with their best moves and style.

A panel of judges scores the dancers based on five criteria: originality, technique, musicality, execution and vocabulary, which refers to the range of moves deployed. It’s somewhat similar to how gymnastics or figure skating are scored, but because of the back-and-forth between the two competitors, breaking involves far more improvisation.

Battles force the athletes to be extremely versatile; they must respond to their competitors, which means that those who have the most robust and varied training protocols are most likely to score the most points and walk away uninjured.

The headspin, in particular, requires powerfully built neck muscles – and might leave some spectators scratching their heads. How can breakers spin on their skulls – supporting the weight of their bodies – without snapping their necks?

The biomechanics of the headspin

While there isn’t a lot of research on the specific mechanics of headspins, a spinning top can help explain how this amazing move is pulled off.

A spinning object maintains its state of rotation due to what’s known as the conservation of angular momentum. When the object spins about a vertical axis, gravity does not act to slow it down or cause it to topple. It is only when friction slows the rotation, or the object starts to wobble, that gravity finishes that job and causes it to fall.

So, to perform a headspin, breakers must ensure they’re spinning fast enough – and ensure their torsos are rigid enough. Maintaining a uniform spin requires stacking the torso as vertically as possible on top of the head and stiffening the neck muscles to support it – all while limiting any bend or strain of the neck.

Breakers can modulate the speed of the spin by bringing their arms and legs closer in or farther away from the rotational axis. They can also stop, start or speed up by pumping their arms.

Breakers can move their arms to speed up and slow down while performing headspins.

As a breaker spins, the rotational forces can actually reduce the downward pressure on the head. There can even be some sliding and shifting across the floor via the head.

A B-boy slides across the dance floor on his head during a performance in New Orleans.

Elite B-boys and B-girls make headspinning look easy, but it puts a lot of load on the neck and can risk serious injuries.

One study showed that while breakers didn’t have more neck flexibility than nonbreakers, they did have significantly more neck strength in all neck motions and in holding the neutral position, which is critical for achieving a headspin. Another study showed that nearly half of all breakers report neck pain and strains.

There’s even a term for a spinal cord injury caused by extreme strain on the neck from breaking that was first described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1985 called “break-dancing neck.”

So, to all those competing on the world stage for the first time, break a leg – just don’t break a neck.

How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession

How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession  Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft

Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft  Trump's Transgender Sports Ban Faces Enforcement Challenges

Trump's Transgender Sports Ban Faces Enforcement Challenges  Trump Draws Cheers at Ryder Cup as U.S. Trails Europe After Opening Day

Trump Draws Cheers at Ryder Cup as U.S. Trails Europe After Opening Day  Australia’s major sports codes are considered not-for-profits – is it time for them to pay up?

Australia’s major sports codes are considered not-for-profits – is it time for them to pay up?  US Reviewing Visa Denial for Venezuelan Little League Team Barred from World Series

US Reviewing Visa Denial for Venezuelan Little League Team Barred from World Series  What makes a good football coach? The reality behind the myths

What makes a good football coach? The reality behind the myths  From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time

From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time  Los Angeles Mayor Says White House Must Reassure Fans Ahead of FIFA World Cup

Los Angeles Mayor Says White House Must Reassure Fans Ahead of FIFA World Cup  Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push

Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push  Trump Plans UFC Event at White House for America’s 250th Anniversary

Trump Plans UFC Event at White House for America’s 250th Anniversary  ‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity

‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity  U.S. Plans $115 Million Counter-Drone Investment to Secure FIFA World Cup and Major National Events

U.S. Plans $115 Million Counter-Drone Investment to Secure FIFA World Cup and Major National Events  Trump Threatens Stadium Deal Over Washington Commanders Name

Trump Threatens Stadium Deal Over Washington Commanders Name  Why the Australian Open’s online tennis coverage looks like a Wii sports game

Why the Australian Open’s online tennis coverage looks like a Wii sports game