The outcome of the UK’s 2019 general election will have lasting consequences. The stark difference in choice between the two main parties pours cold water on the idea that politicians, their manifestos and their electoral campaigns are always “all the same”. Especially when it comes to the economy, there is a massive gulf between Labour and Conservative proposals.

What prompted this election was the inability of parliament to resolve Brexit. Yet the two major parties have devoted little time to actually explaining how Brexit will affect the country’s future. Nonetheless, what is on offer is a clear choice between doing Brexit (the Conservatives) and ending austerity (Labour).

In many ways these two options are inextricably linked, of course. Research shows that parts of the country that were badly affected by austerity saw a large rise in support for the UK Independence Party and Brexit. But, having surveyed the academic literature on the economic effects of Brexit, it is clear that “getting Brexit done” will deeply hurt the UK economy across the board and likely cause austerity to continue.

Nonetheless, the Conservatives promise to “get Brexit done” whatever the cost. All of the party’s candidates pledge to vote for Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal, which was negotiated in October and is currently on the table. The party’s manifesto promises to take the UK out of the EU in January 2020 and not to extend the transition period beyond December 2020. So if no comprehensive future trade deal is in place by this point (as is likely) this would constitute a very hard Brexit.

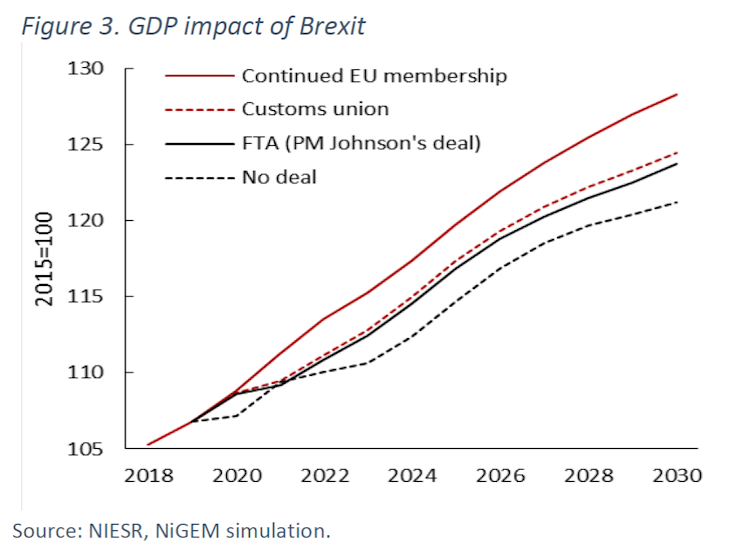

The economic implications of this kind of hard Brexit should not be ignored. As happened following the Brexit vote in June 2016, the pound will depreciate in value. This will lead to increases in prices and lower the value of people’s wages. A slowdown in economic activity will follow, making the UK a less attractive destination for immigration and decreasing domestic and foreign investment. The slowdown in GDP and resulting increase in government spending to make up for it may further hurt the government’s capacity to increase necessary public investment.

Compared to the Conservatives, Labour has been vague about its Brexit plans. It says it will renegotiate the UK’s Brexit deal with the EU and then put this deal to the public in another referendum. The issue here is how long will it take to organise and carry out this second referendum. The longer it takes, the longer uncertainty lingers.

Uncertainty has limited the UK’s economic growth since the Brexit vote in June 2016. Foreign investment is unlikely to recover until investors know what is coming. And immigration from EU countries is also likely to keep falling, which would be bad for a number of sectors. Yet the costs of such lingering uncertainty about whether or not Brexit will be cancelled are much smaller than the certainty of a no-deal Brexit.

Undeliverable spending plans?

Instead of Brexit, Labour has focused on promising to end austerity – a full reversal of the cuts to public spending and investment that have been a key feature of UK government policy since 2010. Its manifesto pledges to increase public investment to levels that are at least four times as high as those planned by the Conservatives. Spending plans for public services like health, police and education, are more than 25 times as big as the (admittedly very small) increases proposed by the Conservatives.

The main criticism of Labour’s plans for the UK economy is that they are undeliverable. If Labour has a majority government and did not pursue Brexit, it could potentially deliver on its spending promises. But this would also depend on the UK economy remaining buoyed by a healthy global economy. So, with trade wars and looming recessions, this may be a lot of “if’s”.

Austerity, ironically, is one of the main reasons for the continuous questioning of whether Labour spending plans can be delivered. The UK government today is much less able to expand its capacity to deliver public services than it was before austerity. Borrowing more is not the whole solution because these spending plans require hiring and training staff, building and updating facilities, as well as planning infrastructure and putting it in place. As overdue or stalled projects such as HS2 and Heathrow’s third runway show, this is easier said than done.

What’s best for the economy

From a purely economic point of view, it is clear that the best policy for the UK is to abandon Brexit and remain in the European Union. There would be a direct economic benefit to staying. Free movement of goods, services, people and capital in the EU has been hugely beneficial for the UK economy. Recent research estimates that these have resulted in UK income per person being about 10% higher. Staying in the EU will resolve uncertainty and it would also make Labour spending plans much more doable.

The range of possibilities for the future relationship between the UK and EU remains is more broad than no Brexit versus no-deal Brexit. There are a range of options in between, including staying in the EU customs union and/or negotiating some kind of free trade deal. The ongoing uncertainty over how this will pan out is a huge challenge for those of us trying to calculate the costs and benefits of the different options.

Yet this uncertainty and the difficulties it creates should not detract from the fact that the final Brexit outcome remains of utmost importance. The economic impact of all the plans the political parties have put in front of UK voters depends crucially on how Brexit is resolved. And voters should be aware that the promise of getting Brexit done comes at a very high price if it means leaving the EU with no deal at the end of 2020.

Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions

Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions  Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns

Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns  Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Asian Markets Surge as Japan Election, Fed Rate Cut Bets, and Tech Rally Lift Global Sentiment

Asian Markets Surge as Japan Election, Fed Rate Cut Bets, and Tech Rally Lift Global Sentiment  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall

Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall  Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding

Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding  Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination

Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination  Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility

Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility  Federal Judge Restores Funding for Gateway Rail Tunnel Project

Federal Judge Restores Funding for Gateway Rail Tunnel Project  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate