From Amsterdam to Manila, Ljubljana to Wellington, the rapid growth of property prices in cities is shutting many people out of home ownership and driving up inequality. There are plenty of ways for governments to deliver more affordable housing, including house-building programmes, taxation, planning and land use regulations. Yet their responses often fall short: government definitions of “affordable” homes aren’t affordable for most, help-to-buy subsidies cause prices to rise further and efforts to boost housing supply fall short of targets.

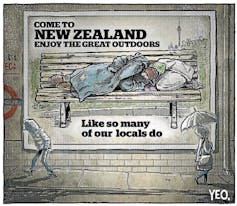

One notable failure occurred in April 2019, when the New Zealand government backtracked on a proposed capital gains tax aimed at tempering speculation in the housing market. New Zealand has a strong case for action: house prices are the third most expensive in the world, the homelessness rate is the highest in the OECD and a quarter of children live below the poverty line – typically in poorly-insulated and overcrowded housing.

The homelessness rate in New Zealand has increased by 25% since 2001, and is now the highest in the OECD. Source: Shaun Yeo Cartoons. All Rights Reserved.

But the opposition deemed the tax to be an assault on the “Kiwi way of life”, the media backlash was unyielding, and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern promised never to pass the policy, while in leadership.

The politics of affordable housing

Failures like this are usually explained by a lack of “political will”. But this excuse simply sidesteps the biggest challenge for politicians: building consensus behind major reforms for the public good. All too often, government decisions to act (or not) are more about maintaining economic and political stability – preferably until the next election. Unless citizens lead strong campaigns to demand action, such reforms will remain in the “too hard” box.

The lack of affordable housing is not a crisis for everyone. Property owners have benefited significantly from the rapid growth in prices, creating highly unequal benefits across class, race and generational divides. Investing in housing is also a cultural norm: many Western cultures see it is as good financial sense to get on the property ladder early, and eventually sell at a much higher price to realise a healthy financial return.

This means that many Western countries have a large cohort of voters who are counting on house price growth – even when that shuts people out of the housing market altogether.

Making change happen

Yet in cities around the world, movements led by citizens are building power to counter these challenges. Here are three examples that show how support can be mobilised, when governments are slow to act.

1. Organising grassroots movements in Berlin

Grassroots movements have a long history in cities, and a recent case from Berlin is instructive. Berlin has a high proportion of renters (85%), and until the mid-2000s, it had a large stock of publicly-owned housing. After public housing was sold off to private investors in the mid-2000s, tenants faced rapid rent increases and significant issues with maintenance and repair.

Public protests march against commercial landlords in Berlin. imago/Christian Mang

Private companies bought public housing on a large scale - the largest landlord, Deutsche Wohnen, owns around 110,000 units in Berlin. Initial efforts by tenants associations to oppose this were no match for the scale of the problem, so they co-ordinated to form the civic movement Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignen (“Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co.”).

The movement demands a referendum that could ultimately allow the municipality to renationalise housing belonging to landlords with more than 3,000 units. This directly confronts the powerful real estate sector, and has great potential to mobilise popular support in a city where renters are the majority. At the time of publication, their petition had more than 77,000 signatures.

2. Building coalitions with technical professions - planners in 1960s New York

Coalitions are the basic unit of urban politics. Building alliances around common agendas is a powerful way to mobilise resources, knowledge and political support. This even extends to professionals like architects and planners, who have historically engaged with communities to advocate for change.

The Urban Underground is a prominent movement that developed from New York’s Department of City Planning in the late 1960s. City planners realised that the profession had been co-opted into regeneration schemes that systematically pushed out black populations and the poor. Protests by local communities and professionals shone a light on these darker aspects of city planning.

Today, some planners are just as complicit in systems that profit real estate developers while causing gentrification and displacement. But with their experience in the system, planning professionals have the power to form a link between the diverse groups affected by unaffordable housing.

3. Demanding system change with a Green New Deal

The last strategy takes inspiration from the US New Deal, which overhauled the economy and social services in the 1930s. The Green New Deal draws from this approach by demanding fundamental changes to the economic system and building support around a vision for the future to resolve trade-offs between economic, social and environmental policies.

‘System change not climate change’, the slogan of the climate justice movement. kris krüg/flickr

The Green New Deal bundles climate action with green jobs, affordable housing and economic justice. Linking climate action to housing might seem unexpected, but in fact it’s central to goals of economic and social justice. It could also be a genius move to wrap housing into the growing political momentum behind climate agendas.

Each of these movements show how change can happen, even when governments are reluctant to take political risks. When communities build support around a vision for housing that works for all – including indigenous populations, people of colour and people living in poverty – they can forge a path for governments to follow.

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  China Overturns Death Sentence of Canadian Robert Schellenberg, Signaling Thaw in Canada-China Relations

China Overturns Death Sentence of Canadian Robert Schellenberg, Signaling Thaw in Canada-China Relations  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy

Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality  Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible

Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible  Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges

Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges  New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients