As Netflix approaches two million subscribers in Australia, free-to-air TV execs have called on government to “ensure a level playing field for Australian media businesses”. The US-based streaming service is alleged to be at an uncompetitive advantage over the established broadcasters, which must follow regulations and legal constraints that do not apply to Netflix. That’s a fair point, and a topic for another column.

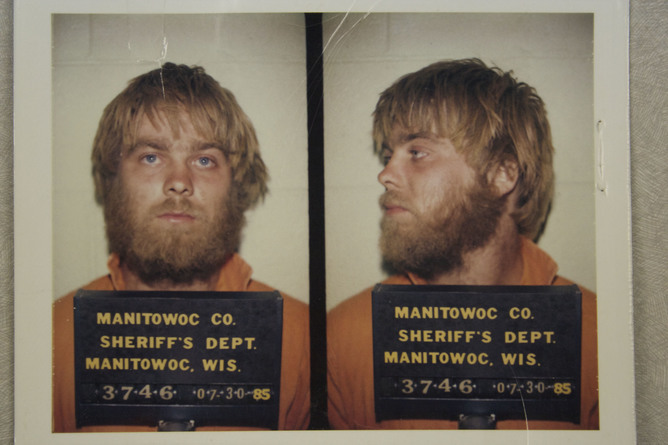

Today, though, I must confess to being one of those two million, attracted not just by the easy accessibility and low cost of Netflix beamed to my Apple TV, or my MacBook Air, or my iPad, at a time and place of my choosing, but the excellence of its original productions such as Making A Murderer.

I completed my binge-watch of Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos’ series just the other day, and it has haunted me ever since. Viewers all over the world have been similarly captivated, using the internet to debate and comment on the series.

Truth, they say, is stranger than fiction, and Making A Murderer demonstrates yet again that media consumers all over the world are drawn to content which is badged as ‘true’.

This isn’t a new trend, although the arrival of online platforms has given a new boost to the cult of what I will call ‘factuality’.

Factuality can be defined as fact-based content which has much in common with investigative and other forms of journalism, but strongy features elements of narrative drama, soap opera, and other fictional formats such as cliff-hanging endings, unexpected plot twists and jaw-dropping moments of revelation (don’t worry – no spoilers for Making A Murderer to come!).

Since the 2000s fact-based media content has been prominent in cinemas, and while feature length documentaries such as Fahrenheit 911 (Michael Moore, 2004), Capturing The Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003), Going Clear (Alex Gibney, 2015) or Man On Wire (James Marsh, 2008) are unlikely to trouble the producers of Star Wars or Star Trek at the box office, they often do just as well as many fictional movie dramas. Moore’s Fahrenheit 911 made $200 million in the US the year it was released, making it one of the most commercially successful films of 2004.

Reality TV shows such as Big Brother have led the primetime TV ratings for two decades, delivering unprecedentedly intimate insights into the ‘real’ worlds of their participants. Even more game show-like variants of the reality genre such as My Kitchen Rules present as in some sense ‘true’ stories.

Except of course that truth, and the facts on which it is built, are never as black and white as we are brought up to believe.

Much of the power of the cult of factuality comes from its problematisation of the very concept of truth, and of reality itself. Where straight journalism clings on to notions such as objectivity, factuality declares that there is no single truth to be learnt about an event – only competing versions, of which more than one may be ‘true’.

Programs such as Making A Murderer and Serial make that quite subtle notion into the stuff of popular entertainment.

In negotiating this inherently postmodern concept of truth, factuality brings us closer to the messy, contradictory world of real people and their dramas than any Woodward and Bernstein could manage.

Making A Murderer tells the story of a mystery, and by the end of its ten episodes the mystery is no closer to being resolved. Rather, audiences are left to ponder the issues for themselves, to debate and post their own versions of the truth online.

In the era of ISIS online progaganda and Putin’s ‘political technology - where the truth about Litvinenko, or MH17, or Ukraine, is what he and his regime-controlled media say it is - I find this turn in capitalist culture encouraging. It speaks of increasingly sophisticated users of media, who not only get the idea of contested reality, of negotiable truth, but thrive on it.

Disclosure

Disclosure

Brian McNair receives funding from the Australian Research Council, and is lead investigator on the Discovery project 'Dissolving Boundaries: journalism and journalists beyond the crisis'. He is Chief Investigator in the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology.

Brian McNair, Professor of Journalism, Media and Communication, Queensland University of Technology

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  Hims & Hers Halts Compounded Semaglutide Pill After FDA Warning

Hims & Hers Halts Compounded Semaglutide Pill After FDA Warning  Trump Threatens Legal Action Against Disney’s ABC Over Jimmy Kimmel’s Return

Trump Threatens Legal Action Against Disney’s ABC Over Jimmy Kimmel’s Return  Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains

Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains  TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans

TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans  SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates

SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates  Washington Post Publisher Will Lewis Steps Down After Layoffs

Washington Post Publisher Will Lewis Steps Down After Layoffs  How Marvel’s Fantastic Four discovered the human in the superhuman

How Marvel’s Fantastic Four discovered the human in the superhuman  FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Testify Before Senate Commerce Committee Amid Disney-ABC Controversy

FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Testify Before Senate Commerce Committee Amid Disney-ABC Controversy  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Face Senate Oversight After Controversy Over Jimmy Kimmel Show

FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Face Senate Oversight After Controversy Over Jimmy Kimmel Show  Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape

Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape  Jazz Ensemble Cancels Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Shows After Trump Renaming Sparks Backlash

Jazz Ensemble Cancels Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Shows After Trump Renaming Sparks Backlash