In the German Bundesliga, crowds have returned to stadiums for the 2020/21 football season. Maximum capacity is between 4,600 and 9,300 depending on stadium size, which equates to between 10% and 25% of the norm. France’s Ligue 1 has made similar steps, with small crowds of 1,000 to 5,000 - if localities do not have special restrictions.

Closer to home, it is a different story. There have been a few pilot games with small crowds of a few hundred fans at some English Football League (EFL) grounds, such as when Charlton Athletic hosted Doncaster Rovers in front of about 1,000 fans on September 19, losing 3-1.

But the UK government announcement of new COVID-19 restrictions in late September paused plans to allow fans to partially return to all matches on October 1. Fans probably won’t now return before April 2021.

It is too soon to see from the recent matches across Europe whether the new procedures and social distancing will sufficiently restrict infection rates to persuade the UK government to change its mind. But even if fans could return to UK sport venues, would they? They might be too worried about safety. The pandemic has also triggered a recession, so many fans will be looking hard at their leisure budgets.

As a result of the global financial crisis of 2007-09, attendance figures at EFL matches fell 10%, according my research in progress with Tunde Buraimo, a sports management specialist at the University of Liverpool, and Giuseppe Migali, an economist at Lancaster University. It is hard to predict what will happen this time around, with concerns around travel and the new COVID-proof match “experience” added to the mix. They clearly might affect gates even after the restrictions are lifted.

Forget gates

English football clubs rely heavily on gate receipts for financial viability. Gates made up 36% of Premier League club revenues in 2018/19, while broadcast revenues and other commercial income such as sponsorship contributed 51% and 13% respectively.

Contrast that with the 72-club EFL, representing tiers two to four, where gate receipts make up the dominant share of revenues. There’s also a massive overall difference in income between the leagues, with average Premier League revenues of £258 million per club compared to £33 million for Championship clubs, £8 million in League One and £4 million in League Two.

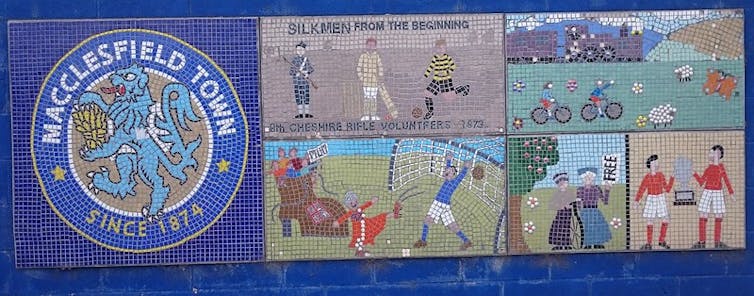

Even before COVID-19, some lower-league clubs were struggling to continue as payrolls exceeded revenues. Bury FC and Macclesfield Town have been wound up in recent months, while Bolton Wanderers and Wigan Athletic received points deductions for going into administration. Relegations quickly followed.

Mosaic at Macclesfield’s Moss Rose stadium. SteHLiverpool, CC BY-SA

The EFL has responded with a strict salary cap for teams in the third and fourth tiers. Yet compelling clubs to play games without paying spectators makes things much worse. Their commercial/sponsorship income is also in danger from sponsors such as airlines, travel and leisure companies cutting their own costs during the recession.

Some in football and other sports are lobbying the government for a bailout similar to the £1.6 billion given to the arts sector over the summer.

Broadcast contrasts

The Bundesliga is the only European football league to strike a new TV deal since COVID-19. It previously had a domestic deal for Germany’s top two tiers worth €4.6 billion (£4.2 billion) over four years. The new Sky Deutschland/DAZN four-year deal kicks off in 2021/22 and is worth €4.4 billion. Industry experts and Bundesliga officials are viewing the slight price reduction as a positive result, considering the severity of the pandemic.

All eyes will be on the English Premier League package, which goes out for tender at the end of 2020. Under the existing three-year deal covering 2019-22, which was worth about £4.5 billion, Sky Sports and BT had to make way for Amazon to broadcast a small number of games in the UK for the first time.

Assuming the broadcasters pay comparable amounts in the belief that viewers will keep subscribing, the revenues will help the 20 top-tier clubs partially recoup what they lose from gate receipts and commercial income. To offset this, the clubs are having to pay the broadcasters a £330 million rebate because of all the disruption to matches caused by the pandemic.

As for the EFL clubs, they sell their broadcast rights separately to the Premier League – most recently in the five-year deal worth just £595 million which runs from 2019-24 and focuses mainly on Championship clubs. Notice the difference with Germany, where the top two tiers sell their rights together.

The question for the EFL – not to mention all lower sports leagues – is to what extent they can make up gate losses through increased match streaming. The EFL is off to a promising start with its iFollow streaming service, which began in 2018/19 with coverage of midweek games. It covers most EFL clubs and is accessed via pay-per-view at around £10 per game through club websites. This season, iFollow has expanded into weekend games.

Another unknown is how games will be affected by the lack of fans in stadiums. The evidence suggests it could reduce “home advantage”, giving away teams a better chance of winning. It is certainly the case that the number of games won in the Bundesliga by visiting teams has increased since COVID-19 restrictions began. Other research across Europe suggests that referees are less likely to give decisions to home teams without fans there. The loss of home advantage could make games more attractive to viewers as away teams are more inclined to press for wins.

One other crumb of comfort for sports clubs is that as the recession bites and companies fold, large and cheap locations will become available for stadium developments. But for English lower-league clubs in particular, the future looks bleak unless the government changes tack on the stadium ban or makes other financial support available.

Robert Simmons does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Robert Simmons does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Japan Economy Poised for Q4 2025 Growth as Investment and Consumption Hold Firm

Japan Economy Poised for Q4 2025 Growth as Investment and Consumption Hold Firm  Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history

Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history  UK Starting Salaries See Strongest Growth in 18 Months as Hiring Sentiment Improves

UK Starting Salaries See Strongest Growth in 18 Months as Hiring Sentiment Improves  U.S. Stock Futures Rise as Markets Brace for Jobs and Inflation Data

U.S. Stock Futures Rise as Markets Brace for Jobs and Inflation Data  NBA Returns to China with Alibaba Partnership and Historic Macau Games

NBA Returns to China with Alibaba Partnership and Historic Macau Games  Australian Household Spending Dips in December as RBA Tightens Policy

Australian Household Spending Dips in December as RBA Tightens Policy  Trump Urges Hall of Fame Induction for Roger Clemens Amid Renewed Debate

Trump Urges Hall of Fame Induction for Roger Clemens Amid Renewed Debate  How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession

How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession  Dollar Near Two-Week High as Stock Rout, AI Concerns and Global Events Drive Market Volatility

Dollar Near Two-Week High as Stock Rout, AI Concerns and Global Events Drive Market Volatility  Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push

Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push  Asian Currencies Stay Rangebound as Yen Firms on Intervention Talk

Asian Currencies Stay Rangebound as Yen Firms on Intervention Talk  Indian Refiners Scale Back Russian Oil Imports as U.S.-India Trade Deal Advances

Indian Refiners Scale Back Russian Oil Imports as U.S.-India Trade Deal Advances  Trump to Host UFC Event at White House on His 80th Birthday

Trump to Host UFC Event at White House on His 80th Birthday  Lee Seung-heon Signals Caution on Rate Hikes, Supports Higher Property Taxes to Cool Korea’s Housing Market

Lee Seung-heon Signals Caution on Rate Hikes, Supports Higher Property Taxes to Cool Korea’s Housing Market  Trump Booed at Club World Cup Final, Praises Pele as Soccer’s GOAT

Trump Booed at Club World Cup Final, Praises Pele as Soccer’s GOAT  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran