When Pacific countries reflect on the state of their media today, marking World Press Freedom Day, they know the reality is much worse than the ticks they got from a global media freedom watchdog last month.

Five of the seven Oceania nations scoped in the Asia-Pacific region scored with apparently significant improvements in the 2019 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Freedom index. Papua New Guinea rose by 15 points to 38th in the global table of 180 countries.

But media freedom advocates know the rankings can be deceptive.

Threats of media regulation

New Zealand rose one place to seventh (to remain in the top 10) and Australia dropped two places to 21st, just one spot above Samoa, which was unchanged but described as “losing its status as a regional press freedom model”. Fiji (52), Timor-Leste (84) and Tonga (45) all “improved”.

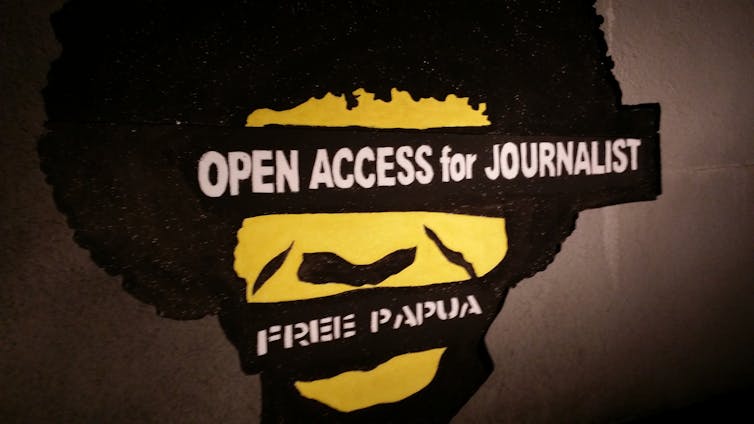

West Papua is the worst situation in the Pacific, but this Melanesian territory is hidden within the Indonesian statistics.

Media freedom in West Papua: a controversial issue in Indonesia but a major concern in the Pacific. David Robie/Pacific Media Centre, CC BY-ND

The RSF index has a robust methodology, and the algorithms reflect that global media freedom has been declining, with growing hostility towards journalists since the last index survey. The situation in the Pacific has also been deteriorating.

While there might not be assassinations, murders, gagging, torture and “disappearances” of journalists in Pacific island states, threats, censorship and a climate of self-censorship are commonplace.

Take Papua New Guinea as an example again. Last week, amid what appeared to be the unravelling of Prime Minister Peter O’Neill’s coalition government, described by many critics as a de facto “dictatorship”, an opposition leader made an extraordinary threat against the country’s two foreign-owned newspapers.

Vanimo-Green MP Belden Namah, leader of the PNG Party which is one of two major groups in the opposition, put the Australian-owned Post-Courier and Malaysian-owned National newspapers “on notice” that an incoming new government would “deal” to the media.

Angered by the two dailies for not running his news conference stories, he threatened to regulate the print media should a new government be installed after the vote of no-confidence due on May 7.

Pressure on journalists

Last November, one of Papua New Guinea’s leading journalists, EMTV’s award-winning Lae bureau chief Scott Waide, was suspended by his company. It had been under pressure from the O’Neill government to have him sacked.

Why? Because he exposed the “inside story” of a diplomatic Chinese tantrum and a scandal over the purchase of luxury Maserati cars during the Asia Pacific Economic Forum (APEC) hosted by Port Moresby.

Columnist Vincent Moses wrote on Pacific Media Watch:

Peter O’Neill is acting like another Chinese dictator in Papua New Guinea by exerting control over both state-owned and private media to not report truths and facts that expose his government and their corrupt acts to PNG and the world.

The strong condemnation that followed forced EMTV to reverse its decision and the network reinstated Waide.

Chiefs demand expulsion of journalist

In the North Pacific, a Pacific Island Times magazine editorial last week blasted traditional chiefs on Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia for demanding the expulsion of a probing US reporter.

Joyce McClure, Yap correspondent for the Pacific Island Times, under fire from traditional chiefs for her reporting. Joyce McClure/Pacific Media Centre, CC BY-ND

The magazine’s editor-in-chief, Mar-Vic Cagurangan, strongly defended her Yap correspondent, Joyce McClure, who has been living on the island for the past three years. She said declaring the correspondent a persona non grata would set a “dangerous precedent”.

Joyce McClure’s reporting provided transparency, which was “vital to every democratic society”, Cagurangan wrote.

Cagurangan has had to defend her team’s journalism before. Last September, she wrote an editorial stressing the tough times Pacific publishers and editors of small publications face dealing with threats from advertisers in tiny markets.

Given the small market, where there is a thin line between business and government, operating a media outlet is much more challenging locally.

Media intimidated in Fiji

In Fiji, the independent New Zealand website Newsroom last month investigated a major environmental development disaster inflicted by the Chinese company Freesoul Real Estate on the remote tourism island of Malolo. The website exposed how Fijian news media had been effectively gagged by 13 years of draconian media legislation and a climate of fear since the 2006 military coup.

Although democracy has returned and two post-coup elections have been held in 2014 and last year, journalists are often intimidated into silence.

Opposition leader Sitiveni Rabuka, the man who staged Fiji’s first two coups in 1987, said the “rot and culture of fear” in the civil service and the “intimidated and cowed media” were now so ingrained in the country that it had taken foreign journalists to break the story.

The RSF media watchdog warned in its 2019 report about totalitarian propaganda, censorship, intimidation, physical violence and cyber-harassment in the Asia-Pacific region. The pressures meant it now took a “lot of courage … to work independently as a journalist” in the region where democracies were struggling to resist various forms of disinformation.

The watchdog singled out China and Vietnam, which both dropped one place to 177th and 178th respectively on the global list of 180 countries, as the worst culprits.

About 30 journalists and media workers are detained in Vietnam, with nearly twice as many being detained in China. The latter country is of major concern to the Pacific in view of its growing economic, aid, trade and strategic influence in the region.

The report says:

China’s anti-democratic model, based on Orwellian high-tech information surveillance and manipulation, is all the more alarming because Beijing is now promoting its adoption internationally.

Mar-Vic Cagurangan, chief editor of the Pacific Island Times. Pacific Island Times/Pacific Media Centre, CC BY-ND

China has embarked on “soft power” strategies of seducing key journalists in the Pacific region with junkets to Beijing where they can be introduced to Chinese media manipulation.

The RSF index sees the growing raft of cyberlaws in the Pacific as an example of this Chinese-inspired media manipulation.

In spite of the pressures, Pacific journalists and publishers like Mar-Vic Cagurangan vow to fight on.

We will continue telling the story and exploring the truth. We are not your enemy. We are your neighbours committed to upholding the principles of democracy.

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary