Massive crowds took to the streets of Iranian cities to mourn the death of Qassem Soleimani, who was killed by a U.S. drone in Iraq on Jan. 3.

State television reported “millions” of Iranians attended the funeral in Tehran on Monday. Images of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei openly weeping over Soleimani’s casket flooded media outlets across the world.

Iranian hard-liners have been keen to use the military commander’s burial to stoke anti-American sentiment in the region and coalesce patriotism around the regime.

Americans need only to look to their own nation’s early history to gain a better appreciation of the powerful tool of mass mourning. What happened in Iran once happened in Boston – and helped lead to a world-changing war.

The history of emotions

Historians have examined how society interprets emotions across different cultures and eras, dissecting a range of feelings from melancholy to love.

Their studies demonstrate that personal feelings are not simply individual experiences. Instead, emotions have important collective cultural and historical weight – and are subject to manipulation and exploitation.

The public displays of grief at Soleimani’s funeral reminded me, as a historian, of powerful emotional performances during the buildup to the American Revolution.

Late 18th-century politics in British North America were awash in feeling. Colonial American forces had played a key role in driving the French from the continent during the Seven Years War, and many Americans resented the new regulations Britain placed on colonists in the war’s aftermath.

News of a far-reaching new tax on printed paper products – including newspapers, legal documents and playing cards – reached the colonies in late 1765. American colonists took to the streets to voice their objections through mournful demonstrations.

As Nicole Eustace outlines in her book on emotions and the coming of the American Revolution, American colonists rang bells and mourned the loss of liberty through mock funeral processions in order to demonstrate their unhappiness.

William Bradford, the publisher of the popular Pennsylvania Journal, printed a funeral edition of his publication, along with a note explaining that his paper was “Expiring: In hopes of Resurrection to Life again.”

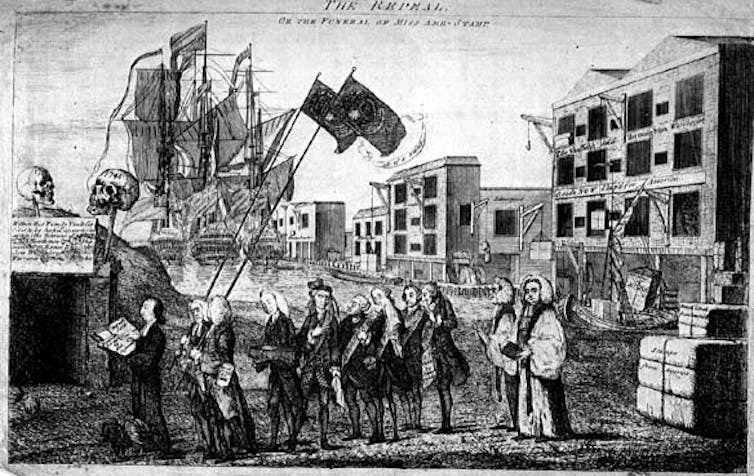

When Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, Benjamin Wilson’s satirical cartoon, “The Repeal, Or The Funeral Of Miss Ame-Stamp,” depicted a funeral for the unpopular bill similar to the mock funerals for liberty that American colonists had organized only a year earlier.

Wilson’s cartoon, published in 1776. Library of Congress

Mourning and the Boston Massacre

While the colonists had used grief to protest unpopular British taxes, these expressions were largely theatrical performances meant to poke fun as much as criticize.

That changed on the night of March 5, 1770, when soldiers of the 29th Regiment of Foot opened fire on a crowd of menacing Boston civilians, killing five and injuring six others.

Led by Colonial agitators Paul Revere and Samuel Adams, Bostonians hostile to British presence in the city named the event the “Bloody Massacre.” They transformed the slain into some of the earliest martyrs of Colonial resistance to Great Britain.

A sensationalized portrayal of the ‘Bloody Massacre.’ Library of Congress

Although the victims came from the lower echelons of Colonial society, Adams provided an extravagant funeral and paid to erect a monument over their graves in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground.

These funerals helped cement anti-British sentiment in Boston and spread similar feelings across the colonies.

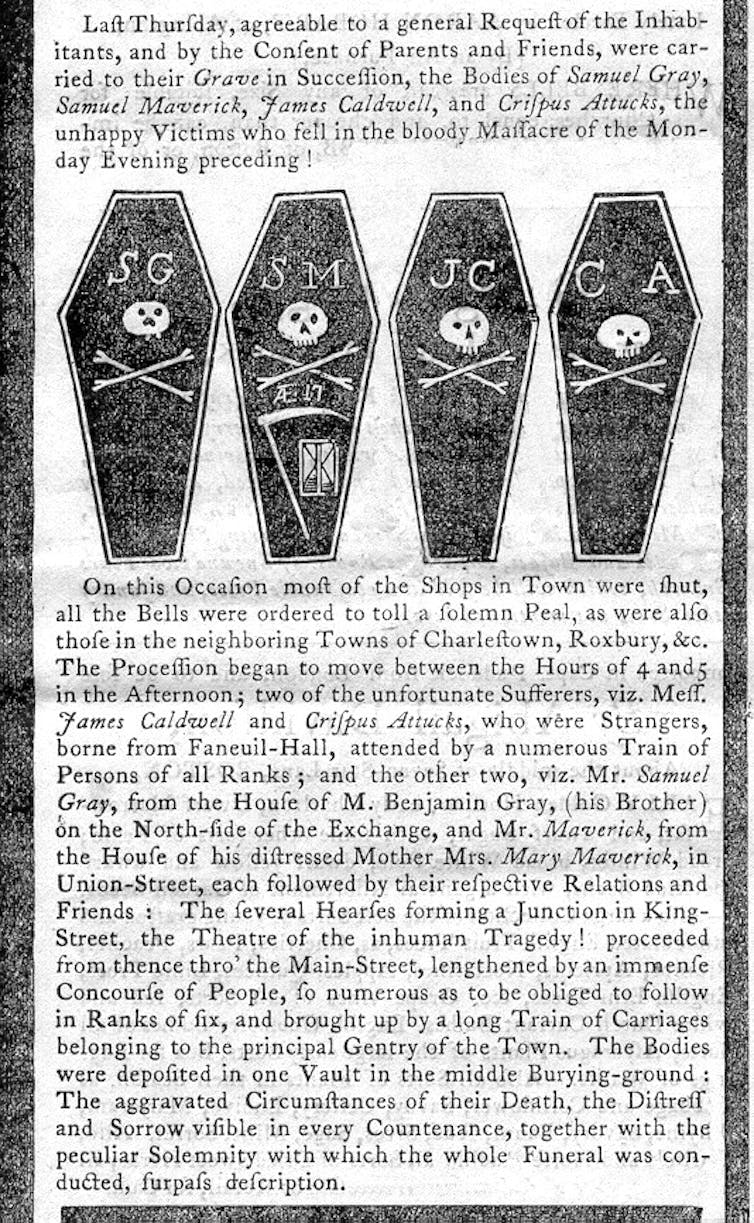

Newspapers recorded that “a numerous train of persons of all ranks” followed the caskets through Boston and was “lengthened by an immense concourse of people so numerous as to be obliged to follow in ranks of six, and bought up by a long train of carriages belonging to the principal gentry of the town.”

The final words from this newspaper account eloquently summarize how this public funeral fueled American passions: “The aggravated circumstances of their death, the distress and sorrow visible in every countenance, together with the peculiar solemnity with which the whole funeral was conducted, surpass description.”

Clipping from The Boston Gazette and Country Journal, from March 12, 1770. Library of Congress

The funeral for the Boston Massacre victims galvanized people from across the colonies against British Colonial rule. The slain had not been men of importance – in fact, John Adams, who defended the accused British soldiers in trial, referred to the crowd that had incited the violence as “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues, and out landish Jack tarrs” – but the feelings that the funeral evoked had the power to bring diverse Colonial people together.

These emotions festered, making a tense atmosphere even more volatile. Ultimately, passions turned into all-out war.

The power of emotions

Some, including Iranian journalist Masih Alinejad, have emphasized that the Iranian government forced many students and officials to attend state-sponsored events, and that demonstrations at Soleimani’s funeral do not accurately reflect his popularity among the Iranian people.

In a press conference on Jan. 8, U.S. President Donald Trump noted that Iran “appears to be standing down.”

But the enduring legacy of the Boston Massacre suggests the powerful emotions related to loss are not easily erased.

Regardless of how Iranians felt about Soleimani in life, his public funeral and the strong emotions it evoked will not soon be forgotten.

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters

Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters  Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University

Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University  Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy

Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy  Ghislaine Maxwell to Invoke Fifth Amendment at House Oversight Committee Deposition

Ghislaine Maxwell to Invoke Fifth Amendment at House Oversight Committee Deposition  Antonio José Seguro Poised for Landslide Win in Portugal Presidential Runoff

Antonio José Seguro Poised for Landslide Win in Portugal Presidential Runoff  Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny

Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny  Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding

Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding  U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains

U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains  Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability

Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability  Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify

Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify