The European Union is preparing to harmonise regulations governing the trade in human milk, which sounds like a good thing. But it won’t be if it sidelines breastfeeding or makes informal human-to-human milk exchanges more difficult.

Women and their families have exchanged human milk informally (including for money) throughout history, and still do.

Until a century ago human milk was mainly delivered in person, breast-to-child, by friends, relatives or wet nurses if mothers couldn’t provide it.

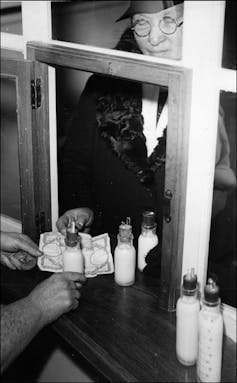

Woman buying milk from nurse at counter, 1939. AP-HP Archives

As the paediatric profession developed, hospitals in Europe and the United States took over the process and began administering human milk by bottles, at first filled by volunteers, and later, in the lead-up to the second world war, by paid donors.

Higher women’s wages after the war made paying donors financially prohibitive, and most countries moved closer to a “gift economy” in which payment for products such as human milk and blood was seen as inappropriate, alongside a growing commercial market for formula and powder derived from cows milk.

Donor milk collected by charities and non-profit organisations from screened donors is mostly pasteurised and tested to minimise risks of disease.

Biotech discovers breast milk

Things changed in 1999 when an American company, Prolacta, developed human milk-based products for fortifying breast milk fed to premature infants.

At first Prolacta didn’t pay donors, but it now pays about US$4 per 100ml for milk it uses to make products that sell for up to US$250 per 100 ml.

In 2015 a not-for-profit Utah-based company, Ambrosia Labs established clinics in Cambodia to collect milk for exporting to the United States.

After the United Nations Children’s Fund condemned the practice saying breast milk could be considered “human tissue” the Cambodian government banned it. Some mothers despaired at losing crucial income.

A few years later in 2017 an Australian-Indian company Neolacta, was granted permission to sell milk collected from Indian mothers in Australia.

In 2019 a related company, NeoKare, established a “state-of-the-art” plant in Europe making freeze-dried fortifier sourced from UK donors.

These human milk product manufacturers are competing with cow-sourced product manufacturers such as Nestle and might soon be competing with start-ups growing new products that mimic human milk.

Industry backs new regulation

The harmonisation being considered by the European Union would extend to human milk the rules that already govern trade in blood, tissues and cells.

Some member states in the European Union already apply tissue and cell rules to human milk, others apply food legislation, and at least 11 don’t regulate it at all.

Australian regulators will be watching closely, because Australian states and territories have similarly diverse rules.

That formula companies are backing the idea provides cause for concern.

But it’s women who matter

Health authorities have already expressed disquiet about commerce-free internet-based milk sharing. The proposal would give them greater powers to act against it.

If these powers were applied heavily they could shut down the generally safe and self-regulated human-to-human trade.

And advancing the medical market for human milk products might delay the advances in social and employment protection policies needed to support breastfeeding at work, at home and in public.

Australian Breastfeeding Association

Human milk is not simply a homogenised “commodity crop in a bottle”.

Breastfeeding creates connections that are important for women’s health and wellbeing and for their babies.

Ironically, where governments fail to adequately protect, promote and support breastfeeding, mothers are often forced to turn to commercial formula for a quick fix.

The proposals as drafted pay scant regard to the United Nations human rights commissioner’s view that “states should do more to support and protect breastfeeding, and end inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes”.

A truly comprehensive set of laws would include protection from marketing and biomedical experiments and allow suitable recompense for donors. Serological testing would be easily available to donors along with guidance to support milk sharing outside of medical facilities.

Such comprehensive laws would impose levies on commercial substitutes in order to fund better breastfeeding support in maternity and newborn facilities.

They would have at their centre the needs and rights of women, who are both the main providers of human milk and (on their children’s behalf) its biggest users.

Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains

Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains  Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding

Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding  Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026

Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026  New York Judge Orders Redrawing of GOP-Held Congressional District

New York Judge Orders Redrawing of GOP-Held Congressional District  Panama Supreme Court Voids Hong Kong Firm’s Panama Canal Port Contracts Over Constitutional Violations

Panama Supreme Court Voids Hong Kong Firm’s Panama Canal Port Contracts Over Constitutional Violations  Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive

Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive  American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns

American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns  Jerome Powell Attends Supreme Court Hearing on Trump Effort to Fire Fed Governor, Calling It Historic

Jerome Powell Attends Supreme Court Hearing on Trump Effort to Fire Fed Governor, Calling It Historic  Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns

Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns  California Sues Trump Administration Over Federal Authority on Sable Offshore Pipelines

California Sues Trump Administration Over Federal Authority on Sable Offshore Pipelines  U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions

U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions  Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine

Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine  Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies  Once Upon a Farm Raises Nearly $198 Million in IPO, Valued at Over $724 Million

Once Upon a Farm Raises Nearly $198 Million in IPO, Valued at Over $724 Million  Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding

Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding