Has the mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry’s origins been solved?

The Bayeux Tapestry is a unique 950-year-old artistic remnant of the Middle Ages that documents the invasion and conquest of England in 1066 by Normans living in northern France.

No one knows definitively why or when the tapestry was made.

Now, new scholarship by Christopher Norton, art history professor emeritus of the University of York, presents evidence that the masterpiece was originally designed specifically to be exhibited in Bayeux Cathedral, probably for its dedication in July 1077.

The textile is long-considered a major cultural icon both in France and England. In light of Norton’s findings, one news source trumpets that the tapestry is definitely French — a conclusion that pierces as “an arrow in the eye” to some British historians.

What is this excitement all about, and why is it important?

Made by English embroiderers

The majority opinion generally agrees that the embroidery was made in England by English embroiderers, sometime between 1067 and 1092.

The first uncontestable documentation of its existence occurs in a 1476 inventory of the treasures of Bayeux Cathedral in Normandy. The tapestry was hung in the cathedral annually until the French Revolution.

Yet despite the tapestry’s documented association with the French cathedral, many scholars argue it would be a better fit with a secular context such as a palace.

The massive textile, measuring 50 cm high and longer than an Olympic-sized swimming pool at 68.45 metres, is housed in the Bayeux Tapestry Museum.

Historical antagonisms

The 11th-century Bayeux tapestry chronicling the Norman conquest of England, in Bayeux, France, in September 2019. (AP Photo/Kamil Zihnioglu)

The Bayeux Tapestry is the subject of an endless flow of commentary and tributes. These highlight how the tapestry is as much an object of fascination for its mysterious origins and formidable craft as it is for the nationalist debates it continues to inspire.

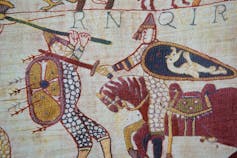

In spite of its name, the Bayeux Tapestry is not woven, but rather consists of 58 scenes, meticulously embroidered with woolen threads stitched onto beige linen cloth. These scenes lead up to the famous Battle of Hastings in southern England on Oct. 14, 1066.

With this campaign, Normans — who were descended from Vikings who had settled in northern France in 911 — conquered England and changed the English social structure and language. It was the last time that the island was successfully invaded by a foreign power, and it had a significant impact on how English society evolved.

The Bayeux Tapestry has attracted an immense following, much of it partisan and fed by historical antagonisms between England and France and beyond.

In the Second World War, because of the Germanic lineage of the Vikings, the tapestry came under Nazi scrutiny. Nazi scholars wanted to adopt it as an Aryan Germanic Viking historical monument.

Cast of characters

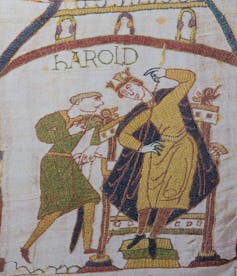

Detail of King Harold. (Shutterstock)

The tapestry’s narrative includes three successive kings of England. These are Edward (the Confessor) who died childless on Jan. 5, 1066, and two ensuing rivals for the throne: his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson (Earl of Wessex), and his illegitimate distant cousin, William (Duke of Normandy).

Images include battle scenes, a funeral, a coronation, two feasts, ship-building, a flotilla crossing the channel, the deaths of two kings, the Norman cavalry, English foot soldiers and many battlefield corpses. Among the cast of named characters is the mysterious Lady Aelfgyva.

Who, why, when?

The 1066 Battle of Hastings was the last time England was successfully invaded by a foreign power. (Shutterstock)

Who made the Bayeux Tapestry, why, when and where are questions that have solicited many conflicting answers. Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, is the favourite candidate for the role of patron, although others have been proposed, including William the Conqueror himself and, traditionally, his wife Queen Matilda.

The tapestry has been interpreted as both pro-Norman and pro-English propaganda. It has been argued that it was meant for a church setting, a great hall in a castle or for a travelling venue.

Norton’s study ties the tapestry more closely to Bayeux Cathedral itself. The designer would have had to have measured the cathedral very carefully, and kept these dimensions in mind when choosing and organizing the depicted scenes.

The proposition that it was meant to be an exact fit with the cathedral’s nave doesn’t necessarily prove a date. But it does narrow the list of possible patrons, and definitely alters how the tapestry’s narrative can be interpreted.

Norton’s arugument would make the tapestry into a triumphal monument for William’s victory.

Counter-arguments have already appeared. In his recent letter to the Times, David Bates, history professor emeritus from the University of East Anglia, pointed out the close connections between the tapestry, Bishop Odo and St. Augustine’s monastery in Canterbury. Bates concludes that the tapestry must be a product of Anglo-French co-operation.

Loan to England

News of the tapestry’s planned exhibition loan to England was heralded by some as the tapestry’s return to England.

This would be an extraordinary event. There have been several earlier failed attempts by England to borrow it, with requests made in 1931, 1953, 1966 and 1972. The requests were rejected either by the city of Bayeux or by the French government, with the fragility of the fabric cited as the main reason.

The anticipated English exhibition motivated Norton to investigate how the tapestry was originally intended to be displayed.

Re-visited evidence

To make his case that the tapestry was designed for Bayeux cathedral, Norton reviewed published archaeological evidence to determine exact measurements of the central nave (public gathering area) of the 11th-century church. The original nave is now encapsulated within the piers and walls of the later Gothic structure.

Nave of Bayeux Cathedral. (Shutterstock)

Norton calculates the original total length of the tapestry (between 71.5 metres and 71.57 metres), including the now-missing final section, to have been about three metres longer than what now exists.

He determines the lengths of the original pieces of linen used by relying on the standard medieval cloth measurement, a unit known as the ell.

Comparing these two measurements, Norton concludes that the tapestry would have fit exactly in the nave of Bayeux Cathedral. He caps his argument by indicating how the scenes on the tapestry were chosen and sequenced to correspond to the piers, door openings, and corners in the nave.

Norton thus suggests a huge rectangular space, about 31.15 metres by 9.25 metres, as the ideal format for the English exhibition, and by extension, for a new viewing space that is being designed and built in Bayeux.

But many factors determine exhibition conditions. It remains to be seen if either locale could commit to that requirement.

In the meantime, the British will have to wait for the conservation assessment that helps determine if it’s safe to move the tapestry and the French government’s final decision. So continues the tapestry’s long-standing intrigue.

Why a ‘rip-off’ degree might be worth the money after all – research study

Why a ‘rip-off’ degree might be worth the money after all – research study  Youth are charting new freshwater futures by learning from the water on the water

Youth are charting new freshwater futures by learning from the water on the water  Debate over H-1B visas shines spotlight on US tech worker shortages

Debate over H-1B visas shines spotlight on US tech worker shortages  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  The ghost of Robodebt – Federal Court rules billions of dollars in welfare debts must be recalculated

The ghost of Robodebt – Federal Court rules billions of dollars in welfare debts must be recalculated  The pandemic is still disrupting young people’s careers

The pandemic is still disrupting young people’s careers  Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice

Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice