It’s been a rocky ride, but a new U.S. president is about to be inaugurated.

Many are thrilled to be moving on from the Donald Trump era, especially after the raid on the U.S. Capitol by angry Trump supporters. But before that happens, it might be worthwhile to reflect on one of the causes of anxiety during the 2020 presidential election campaign: The way votes are allocated in the Electoral College, which is essentially the process by which state electors determine who won the presidential election.

Predominantly liberal commentators argue every four years that it’s profoundly unfair that votes in sparsely inhabited states count for more than those in densely populated ones.

The debate tends to pit those who think the president should be chosen on the basis of the popular vote against those who argue that the Electoral College is necessary to balance the interests of small and large states. But what if there were a third way?

Aimed at compromise

As provided in the U.S. Constitution, the Electoral College serves the necessary purpose of compromising between the divergent interests of various kinds of states (urban versus rural, coastal versus interior, more or less populous).

The problem is not the Electoral College as such, but the “winner-takes-all” principle that most states use to apportion their electoral votes. Sound arguments can be made — and were made during the Constitutional Convention in 1787 — for why, in a federal system, it is fair for tiny Delaware to have a per capita greater impact in presidential elections than populous New York. It’s the same compromise that established equal representation of states in the Senate and their proportional representation based on population in the House of Representatives.

A painting depicting the Constitutional Convention of 1787. (Library of Congress)

What is clearly less fair is for a state to apportion all its electors to a candidate who may not have won even half that state’s popular vote.

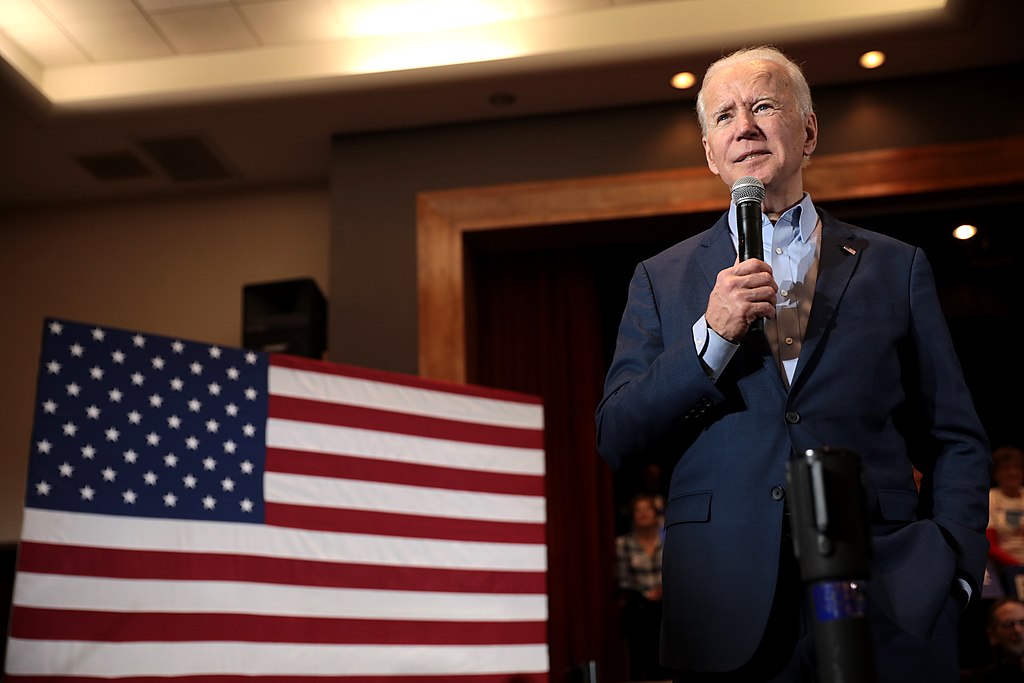

“I know for Iowans it’s disappointing,” Iowa Sen. Joni Ernst said when she acknowledged Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory. But in truth, it was disappointing only for the 53 per cent of Iowans who voted for Trump. Nearly half the state’s population was relieved.

Wouldn’t it be fairer for states to split their votes to reflect the split in their voters’ opinions?

Another way

This is not a reference to the method Maine and Nebraska use — to assign two electors, winner-takes-all, on the basis of the statewide popular vote and one elector based on the vote in each congressional district. Rather, why not eliminate winner-takes-all completely, and simply allocate each state’s electors proportionally to the popular vote in that state?

If this were nationwide practice, Biden would still have won in 2020, Barack Obama would still have won in 2008 and 2012, and George W. Bush would still have won in 2004. But things get more interesting in the two recent presidential elections in which the Electoral College victor did not win the popular vote.

In 2000, Florida would have split its votes 12-12 between Bush and Al Gore without any court needing to intervene, and assigned a 25th elector to Ralph Nader. Bush would have beaten Gore 263 to 262 in the Electoral College, with 13 electors for Nader.

In 2016, Trump and Hillary Clinton would have been tied at 261 electors each, with 14 for Gary Johnson and one each for Evan McMullin and Jill Stein.

The U.S. Constitution of course provides for the event of a tie in the Electoral College. But if states allowed third-party electors to cast their votes for one of the two leading candidates, according the decision of those electors or their state party organizations, the 2000 and 2016 elections could have produced results more closely aligned with the national popular vote while still maintaining equity between small and large states.

All states benefit

The fairness would work both ways. Republicans in California and New York would get a voice, alongside Democrats in Iowa and Arkansas. Votes for third-party candidates would not necessarily be wasted, at least in states with enough electors for small percentages to matter. Most votes would count more, none would count less.

Occasionally, one elector more or less for a given candidate could still hinge on a small number of votes, making recounts necessary, but the stakes would be lower — a single elector, not an entire state’s slate.

Proposals to abolish the Electoral College are ultimately impractical. It’s simply not in the interest of enough states to ever vote for the necessary constitutional amendment. The National Popular Vote Compact — by which signatory states would assign all their electors to the winner of the national popular vote — faces the same impossible hurdle.

But who can argue against the principle that every vote should count?

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics  Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality  Israel Approves West Bank Measures Expanding Settler Land Access

Israel Approves West Bank Measures Expanding Settler Land Access  Bosnian Serb Presidential Rerun Confirms Victory for Dodik Ally Amid Allegations of Irregularities

Bosnian Serb Presidential Rerun Confirms Victory for Dodik Ally Amid Allegations of Irregularities  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Sydney Braces for Pro-Palestine Protests During Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s Visit

Sydney Braces for Pro-Palestine Protests During Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s Visit  Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges

Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges  India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out

India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out  China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit

China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall

Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall  Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape

Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape  Bangladesh Election 2026: A Turning Point After Years of Political Suppression

Bangladesh Election 2026: A Turning Point After Years of Political Suppression  Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny

Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny  US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks

US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks  Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible

Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible