This week we’re exploring nine different policy areas across Australia’s states, as detailed in Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018. Read the other articles in the series here.

Australia has a good health system by international standards, but it has to get better. Half of all patients across Australia wait more than a month for an elective hospital procedure, such as a hip replacement. This is in addition to waiting for an outpatient visit so they can be added to the elective procedure wait list.

“Elective” here doesn’t mean the patient can do without the procedure – they may be in pain or having trouble moving around while waiting. Elective simply means it doesn’t have to be done immediately and can be scheduled.

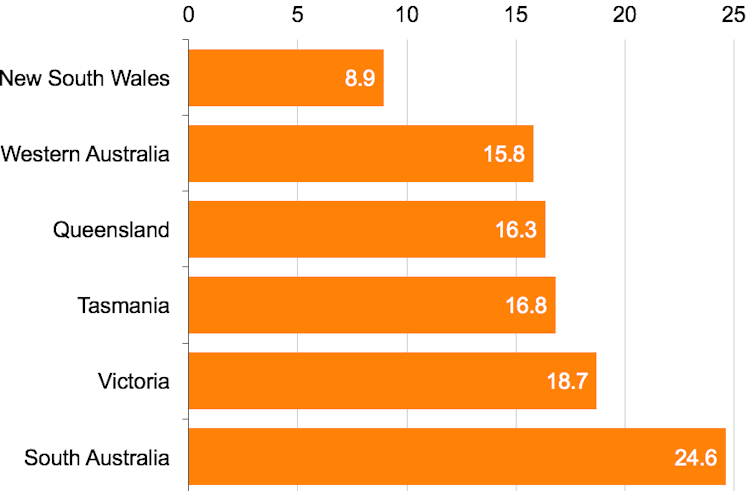

About 9% of people in New South Wales and about 25% in South Australia wait more than a year for public dental services, such as fillings, extractions and root canals.

Physicians report nearly one-third of patients with an acute mental illness wait more than eight hours in hospital emergency departments.

The Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018 charts the performance, maps a route to improvement, and recommends penalties for states that fail to meet waiting list targets.

Why hospitals are always key state election issues

Health is the largest single component of state government expenditure in every state of Australia, and has been growing rapidly. About two-thirds of state government health spending – excluding transfers from the Commonwealth – is on public hospitals.

Just over half the population does not have health insurance and so relies on public hospitals for all their care. Even for people with private insurance, public hospitals are their principal source of emergency care.

State governments are responsible for public hospitals, so hospital care is always a key issue in state elections. It is therefore no surprise state governments love to tell us how much they are doing for public hospitals, and election campaigns are often jam-packed with promises of new or expanded hospitals.

The politicians, at least in states with growing populations, are right that more beds are needed. What matters for the public, though, is not how many beds there are, but whether there are enough. One way of measuring that is waiting times, and here the picture isn’t as rosy as campaigning politicians would like us to believe.

Waiting for elective hospital procedures

It’s bad enough half of all patients across Australia wait more than a month for an elective procedure from the time they were booked. What’s worse is that about 10% wait more than six months.

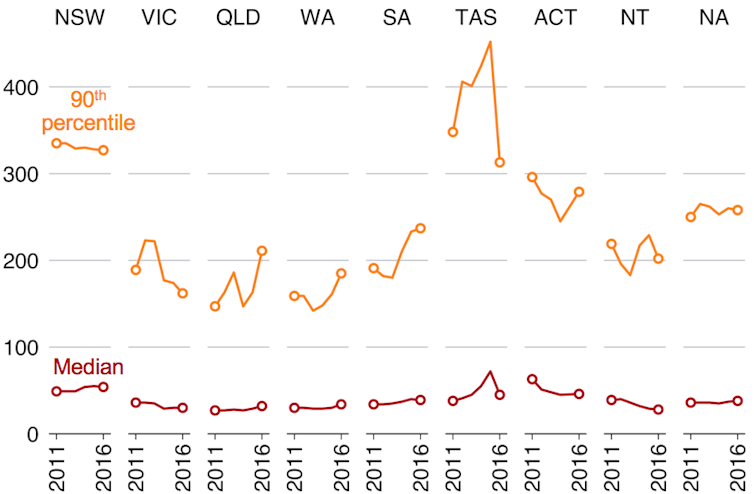

In our smallest state, Tasmania, 10% of patients wait about a year. In the biggest state, NSW, the situation is almost as bad.

This graph shows the waiting time (days) for elective procedures, 2012-13 to 2016-17, for the 10% of patients who wait longest (orange) and the median (maroon):

Grattan Institute/Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Publicly reported data focus on elective procedure or elective surgery waiting times, but there is another important wait: from the time a patient is referred to the hospital to the time they are seen in an outpatient clinic. This is sometimes called the “hidden waiting list”.

For the patient, the wait for an appointment with an outpatient clinic matters – it delays diagnosis and treatment. Yet these waits are not publicly reported in NSW, Western Australia, the Australian Capital Territory or the Northern Territory. And the states that do report outpatient clinic wait times do not use consistent measures.

Our state and territory governments should strengthen hospital accountability to reduce combined outpatient and inpatient waiting times. There should be clear consequences and penalties for failure to meet targets.

Waiting for public dental care

The COAG Health Council (made up of Commonwealth, state and territory health officials) says current funding for public dental services allows for treatment of only about 20% of the eligible population.

The remaining 80% have to wait for long periods, pay for relatively expensive care in the private sector, or go without care entirely.

Waiting times vary significantly among states. And in several states, notably Vic and SA, waiting times have got longer in recent years.

Boosting public dental services will improve people’s health and reduce the strain on hospitals.

In 2015-16, there were 67,266 hospital admissions for potentially preventable dental conditions – more than one-fifth of all hospital admissions for potentially preventable acute conditions.

Unforgivably, our state governments have not delivered on a 2012 commitment to monitor waiting times for public dental care through a National Healthcare Agreement performance indicator. Data inconsistencies mean it is not possible to reliably compare public dental waiting lists across states and territories.

NSW does not provide data on public dental waiting lists at all, citing concerns about the potential for misleading comparisons. The only comparable data we have is from an Australian Bureau of Statistics sample survey, which shows more than 10% of patients across the country wait more than a year for public dental care.

This graph shows the proportion of people who waited more than a year for public dental services:

Notes: The figures in smaller states should be regarded as approximate; the percentages are of those who have been seen, and do not include those still waiting at the time of the survey. Grattan Institute/Australian Bureau of Statistics

Waiting for mental health care

Campaigners say Australia has reached a “tipping point” on access to mental health care. Physicians report nearly one-third of patients with an acute mental illness wait more than eight hours in emergency departments.

We know this does damage: long waits for access to community mental health services can result in poorer outcomes for patients, as a condition may be harder to control the longer it persists. Long waits may also place additional pressure on families or friends who face the consequences of their friend or family member’s behaviour.

Yet there is no information about the adequacy of community mental health services in Australia. The 2017 National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan only tracks the use of services, not their adequacy.

In contrast, Canadian governments have agreed that a wide range of mental health and addictions indicators will be collected and reported from 2019.

Australian voters should demand their state governments do the same thing. We should wait no longer for a better health system.

Royalty Pharma Stock Rises After Acquiring Full Evrysdi Royalty Rights from PTC Therapeutics

Royalty Pharma Stock Rises After Acquiring Full Evrysdi Royalty Rights from PTC Therapeutics  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Sanofi Gains China Approval for Myqorzo and Redemplo, Strengthening Rare Disease Portfolio

Sanofi Gains China Approval for Myqorzo and Redemplo, Strengthening Rare Disease Portfolio  FDA Targets Hims & Hers Over $49 Weight-Loss Pill, Raising Legal and Safety Concerns

FDA Targets Hims & Hers Over $49 Weight-Loss Pill, Raising Legal and Safety Concerns  Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China, Boosting Access to Wegovy and Mounjaro

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China, Boosting Access to Wegovy and Mounjaro