The legal status of cannabis, and in particular its medicinal benefits, have been much debated in parliament and the press in recent months. During this time, we have been interviewing police officers in North Yorkshire, England, about the day-to-day policing of cannabis possession. We’ve also analysed anonymised data on 4,597 drug possession offences during 2013-16. This research raises important questions about how police forces in England and Wales should deal with this common but to some, trivial, offence.

Cannabis possession made up nearly three quarters of total drug offences in the North Yorkshire Police Force area during the period of our research. Yet, most of the 37 police constables and sergeants we interviewed across six police stations thought that their policing of cannabis possession had little or no long term impact on offenders’ drug use.

Nonetheless, they saw it as their duty to enforce the law – and, importantly, to be seen to enforce the law. Officers spoke about the need to fulfil public expectations that action would always be taken where a law is clearly being broken.

Some also thought that, on rare occasions, they could have an impact on some cannabis users, particularly young people, by preventing escalation to more serious drug use or offences; or preventing mental health problems. Officers were generally of the opinion that the long term harms and links to criminality they associated with cannabis use required them to take positive action when they came across the drug.

We also found that cannabis policing often appeared to be accidental. Rarely did officers proactively seek out cannabis possession offences. Instead, cannabis or evidence of cannabis use was most frequently found in the course of unrelated policing activity: for example, where officers stopped a car that had raised suspicions for other reasons, and a cloud of cannabis smoke had been released when the car window was wound down.

However, there was almost universal agreement among officers that, whatever the nature of the offence, formal action should always be taken. It was not seen as acceptable for officers to deal with the situation informally by simply dropping the drug down a drain. This is in marked contrast to previous UK research which found that police officers frequently simply confiscated small amounts of cannabis and destroyed them in front of the user.

Smells like weed

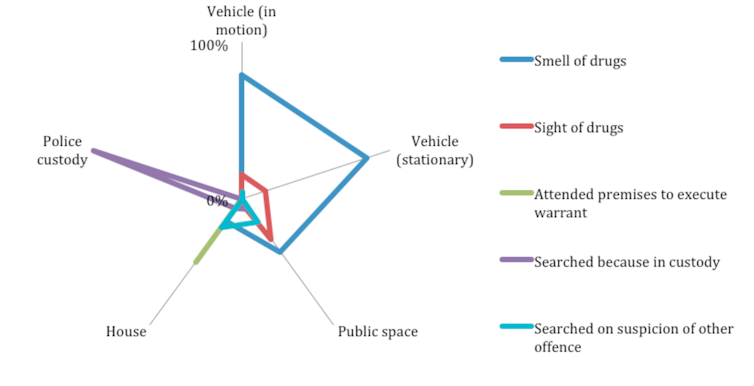

The issue of smell was significant. In approximately half of all cases where an explanation for a search was given, smell was cited as the reason. In some situations, the proportion was considerably higher, as the diagram below shows.

The reasons officers give for searching people, in different contexts. Authors provided.

Guidance from the College of Policing states that the smell of cannabis on its own will not normally justify a search – but yet a third of our interviewed officers thought that it did.

Among some of the officers who were aware of the guidance, there was frustration with the idea that a strong and obvious smell of cannabis was not sufficient sole grounds for a search. It’s possible that changes in the nature of cannabis may be affecting this issue. Strong strains of herbal cannabis such as “skunk” which have a very pungent smell may be making public consumption of the drug much harder to hide; and therefore much harder for police officers to ignore.

Reflecting a long history of research on the targeting of stop and search, our study found a strong relationship between deprivation and apprehension for cannabis possession. Even though very few offenders were encountered in their home wards, people both in and from more deprived wards were significantly more likely to be sanctioned for cannabis possession.

Warnings first

Many officers were keen not to criminalise cannabis users, particularly younger users, and therefore welcomed the fact that there were a number of steps before a repeat offender would be charged with a possession offence. Cannabis warnings, which involve confiscation of the drug and the filling out of a short form for adults, were largely popular with officers, some of whom saw scope for expanding their use to 16- and 17-year-olds.

So it’s concerning that the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s new strategy on “out of court disposals” – alternatives to prosecution such as early interventions and cautions – could lead to more rapid criminalisation of cannabis offenders.

Until now, arrest should in most circumstances only occur at someone’s third offence: after the police have given a cannabis warning and a fine for previous offences. The new strategy could see cannabis warnings abandoned as an option for first cannabis possession offences. While forces around the country are interpreting this in various ways, the strategy suggests that a person caught in possession twice within a 12-month period would be given a conditional caution for their second offence, which would constitute a criminal record. This approach represents a swifter criminalisation for people accidentally found by the police to be in possession of small amounts of cannabis than was formerly the case.

Officers in our study were acutely aware that the long term consequences of having a criminal record might be disproportionate to the seriousness of these offences

At a time of decreasing recorded drug offences nationally and in North Yorkshire, many officers felt that low police officer numbers had had a significant impact on their ability to proactively police cannabis possession. Given that the police are under increasing pressure and “managing demand” is much discussed, it may be the time to look again at the policing of cannabis possession and whether this is something on which society wants its police forces to spend their valuable time.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding

Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding  Federal Judge Blocks Trump Administration Move to End TPS for Haitian Immigrants

Federal Judge Blocks Trump Administration Move to End TPS for Haitian Immigrants  Federal Judge Signals Possible Dismissal of xAI Lawsuit Against OpenAI

Federal Judge Signals Possible Dismissal of xAI Lawsuit Against OpenAI  Federal Reserve Faces Subpoena Delay Amid Investigation Into Chair Jerome Powell

Federal Reserve Faces Subpoena Delay Amid Investigation Into Chair Jerome Powell  Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding

Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?