Naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace’s collecting expedition in Southeast Asia between 1854 and 1862 is rightly famous. His historic discoveries remain important today. These discoveries include the greatest division between animal groups in the entire region, now called the Wallace Line, and inspired a theory of evolution by natural selection.

Wallace was the first naturalist to visit many islands. He discovered countless new facts about animal behaviour and distribution and thousands of species new to science. Most accounts of his voyage mention his impressive collection total of 125,660 specimens of mammals, reptiles, birds, shells and insects.

His book The Malay Archipelago (1869) has inspired generations of naturalists and travellers. It is well known that he paid assistants called Charles Allen and a young man named Ali from Sarawak. But it has never been appreciated just how large a role local people played in Wallace’s voyage and collections.

By scouring Wallace’s publications, letters and notebooks with a different focus on the help he mentions, the true scale of the role of local people shows us something new and important about Wallace’s voyage. His results and successes would have been impossible without the help of hundreds of local people.

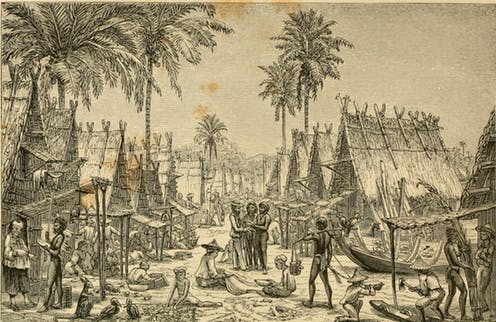

Not every person Wallace hired to shoot birds, to cook, to paddle a boat, to bring him animals or work as porters, guides or translators was recorded. While the exact number can never be known, we can still glean the approximate number of helpers at a given location, based on the written sources that survive. A few examples can illustrate some of the kinds of essential assistance Wallace received.

While staying at a village outside Makassar, Wallace made an offer to the local children. If they would “bring me shells & insects they might also get a good many [coins]”. Wallace eventually received many “beetles & shells that my little corps of collectors now daily brought me”.

On Seram he employed “a lad from Awaiya who was accustomed to catch butterflies for me”. A man from Langowan, Sulawesi, procured Wallace the White-Bellied Imperial-Pigeon (Ducula forsteni), which he “had long been seeking after”.

White-bellied Imperial-Pigeon. SandyCole via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

During his two-month stay on Buru, Wallace was assisted by a local rajah, 16 rowers, eight Alfuro men who carried his baggage and two men he paid to make a clearing in the forest, which produced many good insects for his collection.

Local people also gave him information about birds on the Sula Islands, which he recorded in a notebook. The knowledge of local people was absolutely essential for Wallace. They often told him where to look for types that he had not yet found.

Here is a breakdown of the approximate number of local people who helped Wallace at his principal collecting sites.

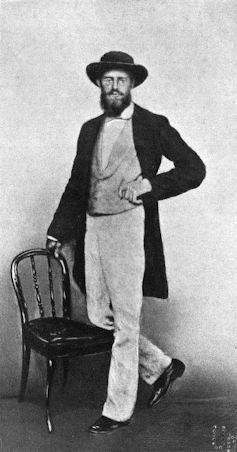

There were many differences between Wallace and his assistants. He was from a faraway industrialised country. He was well educated. He could read English, French and Latin. (He also learned to speak Malay.) He knew a great deal about the sciences.

Photograph of Alfred Russel Wallace, taken in Singapore, 1862. Marchant, James (1916) Alfred Russel Wallace — Letters and Reminiscences, Vol. 1, London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell and Company via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

But despite the differences, Wallace was, like his helpers, a young man making his own way in the world. He was making a living. And Wallace too was working for others because the collectors and museums back home were buying his specimens and paying his way.

The veritable army of people who assisted Wallace in so many ways during his voyage is testament to his ability to interact successfully with people of many different cultures. It also testifies to his amiability and ability to evoke sympathy and a desire to help this strange foreigner interested in collecting apparently worthless dead animals.

Wallace was not a lone genius or, as the popular sound bite has emerged and become ubiquitous in the last 20 years, “the greatest field biologist of the 19th century”.

Wallace was not a field biologist. This is a modern concept. He was a Victorian specimen collector and naturalist. They are not the same thing.

Equally, we would not refer to him as a scientist, another term not then in use and which connotes workers of a different age and culture. Wallace lived and worked before the age of professionalised science.

But what we can now appreciate is that at the very least 1,210 people, mostly residents of what is now Indonesia, helped Wallace achieve what he did. Because of the incompleteness of the written record, the true number could easily have been more than twice this number. Wallace was not alone.

This article is an edited excerpt from “Wallace’s Help: The Many People Who Aided A.R. Wallace in the Malay Archipelago” in the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer  Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate

Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost

As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research  Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world

Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world  Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history

Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history  We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing

We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing  Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys

Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys  How America courted increasingly destructive wildfires − and what that means for protecting homes today

How America courted increasingly destructive wildfires − and what that means for protecting homes today