As the “Weinstein effect” sweeps Hollywood, the sex/gender/pop culture clash that is my passion project has led to lots of conversations, oftentimes on air. At some point during interviews there’ll be a question about change: about whether there’ll be any “lasting impact” from the deluge of recent revelations.

A good question and a nebulous one.

The immediate impact is one of data collection: of women - and, in smaller numbers, men - disclosing stories of gross misconduct committed by men in positions of power, of influence.

For every woman who tells her tale on CNN though, for every woman who divulges her hurt in social media, and for every woman watching on with a secret stash of her own unspilled stories, a picture emerges of prevalence. That this bullshit has - in varying degrees - haunted the lives of all women and that something must change.

But what happens beyond the sharing?

A couple of weeks ago I was awaiting a session of The Snowman. (N.B. Save your money). I was using the time to read a Medium article that presented a list of Hollywood men who’ve been accused of crimes against women. (Most on the list haven’t admitted anything).

Snowman star, Michael Fassbender coincidentally happened to be named and shamed.

The Medium article didn’t impact my viewing experience - I’ve written previously about the necessity to separate art from artist; see here and here - but the list nonetheless niggled. It niggled throughout every gaping Snowman plot hole and it niggles two weeks on.

The “Weinstein effect” taps into my interest in sex, gender and pop culture. But equally so, it creates an unhappy frottage between two other interests: my belief in victims rights to tell their own stories vs. my apprehensions about trial by Twitter.

Earlier this year a report documented sexual harassment in Australian universities. In interviews I did in the aftermath, as well in conversations had with colleagues - male ones most commonly - concerns about methodology were raised.

How was the data collected?

What agreed upon definitions were used?

How big was the sample size?

As a social scientist I’ll always agree that for a survey to be useful - for it to be considered “gold standard” - the data needs to be collected rigorously. As a feminist though, and as a woman, I also agree that women’s voices have - for time immemorial - being silenced because they’re seemingly not speaking, not airing their grievances, on men’s terms.

There might have been better ways of gathering the data, sure, but there exists no perfect collection method - it’s why good methodologies always address limitations. Equally, those who don’t want to believe women will always find an excuse to minimise their harm: rape myths exist because there are people religiously dedicated to distrusting women.

When victims come forward with their stories we have to believe them. We have a duty to take them at their word primarily because speaking out against patriarchy in a culture where patriarchy has a vested - and virulent - interest in ensuring silence is brave, is risky.

But what of the alleged but untried assailants? What do we make of careers being ruined purely on the basis of “mere” allegations?

Here’s where things get complicated.

The naming and shaming of men who haven’t been charged - let alone seen the inside of a courtroom - is, to put it mildly, disconcerting. That said, we happen to live in a world where women frequently don’t report their abuse and on those rare times when they do, the likelihood of the perp appearing before a judge - let alone being locked in a prison cell - is minuscule.

In light of these unpleasant culture and law enforcement realities, can I - in good faith - suggest that women are best off waiting for the proverbial “slow wheels of justice” to, ultimately, fail them rather than see them tell their story - to name their perp - in social media?

I don’t have an answer and I’ll remain conflicted about this mash-up of necessary story-telling, important consciousness-raising and my severe discomfort with vigilante justice.

I started this article mentioning impact and there I shall return.

The impact of any social change campaign is difficult to measure. Not only do we need to measure change over time, but even very good data doesn’t offer the clearest of pictures. A spike in police reports can indicate greater instances of a crime. The same data however, can just as easily highlight the success of campaigns to actively encourage reporting. Countries with very low numbers of reported rapes aren’t always countries with genuinely low numbers of rape.

Nonetheless, in recent days we’ve seen some actions that at least look a little like impact.

We’ve seen Netflix fire Kevin Spacey. We’ve had Sony go so far as to edit him out of a completed film and replace him with Captain von Trapp. HBO are scampering to distance themselves from Louis C.K.

On one hand these are measurable impacts: men who’ve allegedly done heinous things are being punished where it hurts them - their pride, their reputation, their hip-pocket.

On the other hand, it’s worth questioning whether Netflix, Sony and HBO are doing this because they believe and support the victims, or because they are businesses and businesses care, most of all about money.

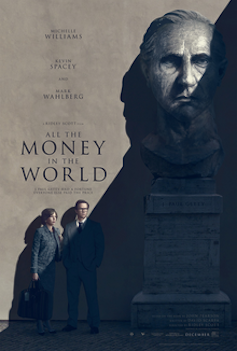

Was the stink-brand of Kevin Spacey, for example, going to ruin any chances of All the Money in the World making a motza at the box office? Was keeping Louis C.K. on air going to make HBO look like abetters?

I recognise that a lot of good feminist policies - think sexual harassment legislation and paid parental leave - couple good works and good economics. So while it’s easy to be cynical about economic motivations we should also be open to the possibility of true industry change resulting.

I’d be remiss however, if I didn’t note my hesitation. Men don’t sexually harass in a vacuum. Invariably those around them - notably those lining their pockets as a star rises - facilitate misdeeds: think silence, ignorance, assistance, intimidation.

Powerful and influential perps often get away with their crimes because there are many folks around them protecting and ensuring their untouchability.

Whilst the Weinstein Company was raking in the dosh and winning all the Oscars, is it any surprise that Horrible Harvey wasn’t outed earlier? It is for this reason we need to be reserved in our lauding of companies. Some of this stuff happened on their watch and was allowed to go on, unchecked, for years before it went public.

Punishing perps is one thing, making sure no man has enough power to take a meeting in a bloody bathrobe is another.

Impact is a difficult beast to test and scalps are only one measure. In industries that frequently treat women like meat - when women are routinely sexualised and objectified via crap roles constituting little more than eye candy - there’s a deluge of work to be done before true cultural change revolutionises the industry.

Federal Judge Signals Possible Dismissal of xAI Lawsuit Against OpenAI

Federal Judge Signals Possible Dismissal of xAI Lawsuit Against OpenAI  Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action

Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action  Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies  Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive

Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive  Trump Lawsuit Against JPMorgan Signals Rising Tensions Between Wall Street and the White House

Trump Lawsuit Against JPMorgan Signals Rising Tensions Between Wall Street and the White House  Panama Supreme Court Voids Hong Kong Firm’s Panama Canal Port Contracts Over Constitutional Violations

Panama Supreme Court Voids Hong Kong Firm’s Panama Canal Port Contracts Over Constitutional Violations  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links

Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links  California Sues Trump Administration Over Federal Authority on Sable Offshore Pipelines

California Sues Trump Administration Over Federal Authority on Sable Offshore Pipelines  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday