China often makes headlines on a great variety of topics, yet very little is said and known about its contested heritage. At a time when this country with a complex and rich history is undergoing rapid urbanisation, one might expect contested heritage to be a hot topic.

For example, many Chinese scholars, officials and villagers view heritage preservation and display as tools of modernisation and improvement in “backward” rural areas. Therefore, the project of cultural heritage display becomes a colonising project, one that estranges local communities from their own cultural resources. In that case, the display of cultural heritage in rural China becomes a contested project.

The village of Tunpu in Guizhou province is a distinctive example of this. The language and culture of Tunpu are not derived from local villagers, but are defined by scholars to represent villagers.

More urbanised areas, notably Hong Kong, also have many cases of contested heritage. The city has a long British colonial history and returned to China in 1997. Many cultural heritage sites remained. These including the Marine Police Headquarter Compound, the Star Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier, and the Central Police Station Compound.

Nowadays, in the development of Hong Kong, there are differences between the governor and the community in interpretation, restoration, preservation, assignment, commodification or elimination of these heritages.

What exactly do we mean by contested heritage?

Interestingly, an international literature review produces no clear definition of contested heritage. Rather, there is a consensus on its common characteristics.

Firstly, the value and meaning to be given to a specific heritage are contested. Most of the time this is because there are different views and conflicts on aspects of this heritage during its preservation, redevelopment or urban restoration. For example, this happened when deciding the future of the Nazis’ Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. It eventually became an educational tourism destination.

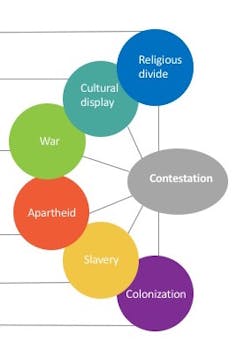

Contestation over heritage has many origins, but always involves negative sentiments. Karine Dupré, Author provided

Secondly, contested heritage sites always convey a negative sentiment to some extent. Think, for instance, of a walled city: those living either side of the wall will have different attitudes to it. These contested heritage sites are about colonisation, apartheid, slavery, conflict and war, and religious divides.

Although in postcolonial settings multiple communities can succeed in sharing a common negative heritage and become resilient about it, the heritage left by war is always contested, since different countries have different positions. For instance, Japan, America and China have different views of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome), which was inscribed on the World Heritage List. America and China opposed the nomination but for different reasons.

Finally, interpretations of contested heritage by different interest groups fluctuate as these interpretations and meanings might vary depending on the historical period. This is obvious in how the terminology has evolved. It was previously discussed as dissonant heritage and later as ambivalent heritage and even negative heritage.

So what about China’s contested heritage?

As a country with a very long history, China is rich in heritage. It already has 36 cultural heritage sites and four mixed heritage sites on the World Heritage List.

Yet the modern Chinese consciousness of cultural heritage protection began in the late 19th century. This was closely related to Western influence on China at that time (Guo, 2009). That is once source of contested heritage today.

Other contested heritage relates to the traces left by Russian and Japanese colonisation of China. There has been a shift in national heritage policies and in the handling of such memories.

Dalian, on the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, is a good example. Like Hong Kong, Shanghai and Qingdao, Dalian’s development stemmed from colonial occupation. Invaded by the Russians in 1897, the Japanese in 1905 and returned to China in 1955, the city went through half a century of colonial rule.

This has left lasting imprints on Dalian’s urban planning and urban landscapes. Basically, these are either highly valued (the Russian Nikolayev Square main square is heritage-listed), targeted for demolition, or dismissed (low-income districts built under Japanese rule) … until recently.

Model of Dalian’s historical main square. Courtesy of Dalian Urban Planning Museum, Author provided

A more nuanced view of heritage

Attention to contested heritage is quite recent in China. There is still little discussion about it as urban modernisation has for a very long time been the number one priority.

However, with rising awareness of the cultural and economic benefits that some heritage could bring to communities, as seen in Dalian, the debate about contested heritage has been gradually gaining more prominence. This is important as it contributes to rewriting the national narrative with more shades of grey.

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary