New national security measures proposed by China would significantly undermine the rule of law in Hong Kong, limiting freedom of speech, restricting the right to due process and curtailing other basic civil liberties. The stakes are high for the Hong Kong people, who’ve been fiercely defending their autonomy from the Chinese government for years.

The greater respect for human rights and the rule of law that distinguishes this former British colony from mainland China stems, in part, from a little known chapter of Hong Kong’s history.

Between 1975 and 1997, almost 200,000 Vietnamese sought refuge in Hong Kong, fleeing from their communist government. The majority were eventually resettled in the United States, Canada and Australia, but tens of thousands were stuck in Hong Kong camps, often for years, waiting for their asylum claims to be processed.

Some Vietnamese activists in the camps accused Hong Kong of violating their human rights. In making their case in court, they actually helped define the terms of Hong Kong’s current struggle with China.

‘Please help the boat people!’

“Have you ever lived under a communist regime?” a Vietnamese man asked United Nations officials in July 1989, when huge numbers of Vietnamese were arriving in Hong Kong.

“Look at the T.A.M.” he added, referring to the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Weeks before, on June 4, 1989, Chinese soldiers had killed student protesters en masse at Tiananmen Square. For the man, who had just arrived in Hong Kong, citing this grim example to UN human rights officials in an effort to get refugee status must have seemed strategic.

Aware that Hong Kong people would be observing the crackdown in communist China, the Vietnamese might have imagined the government there would understand why he had fled a communist country.

Even as Hong Kong received an influx of Vietnamese people in the late 1980s, Great Britain was actually negotiating the return of the territory it had acquired in the 1840s back to China. Hong Kong people worried they would lose their economic and political freedoms in that transition.

Their concern about life under communist rule did not, however, translate into much sympathy for the Vietnamese arrivals. Many Hong Kong people resented that Vietnamese had been welcome as refugees simply because they fled communism, when unauthorized Chinese border crossers were promptly returned back to China.

In 1988 Hong Kong changed its asylum determination process, requiring Vietnamese claimants to prove that they had faced targeted political persecution back home. This is what led to the lengthy detentions of thousands – and, consequently, to allegations of human rights violations.

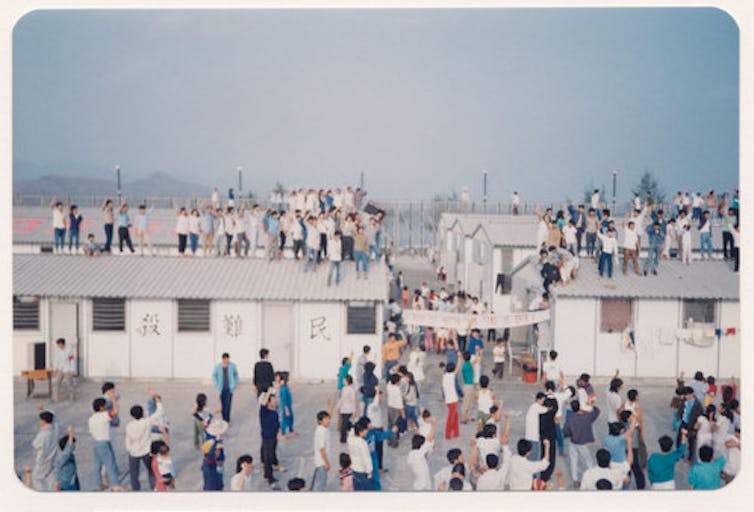

As negotiations around the 1997 handover progressed, Vietnamese activists in the camps led dozens of protests, hunger strikes and demonstrations. In tense standoffs within the camps, Vietnamese shouted, “Protest against forced repatriation! Protest against the violation of human rights! The people of Hong Kong, please help the boat people!”

Habeas corpus

As I recount in my new book, “In Camps: Vietnamese Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Repatriates,” legal advocates for the Vietnamese brought dozens of lawsuits before Hong Kong’s courts in the 1990s, pointing out the flaws in the asylum process.

Finally, in 1995, Hong Kong-based lawyers devised a new strategy to free clients who were still in limbo. They began filing habeas corpus petitions, invoking a bedrock principle in western law that protects individuals from indefinite detention or being detained without knowing the charges.

In one habeas motion, Hong Kong human rights lawyers representing three Vietnamese families who had been detained for more than four years said this was an “extraordinary” amount of time, and argued that the Hong Kong government must release their clients.

Pointing to the rapidly approaching handover to China, the lawyers told the South China Morning Post that the case had implications for “the future of civil liberties for everyone in Hong Kong after 1997.”

If Hong Kong leaders wanted guarantees that its people would maintain their civil and economic liberties under Chinese rule, the lawyers suggested, the fact that Hong Kong itself was holding people “in administrative custody indefinitely” could set a dangerous precedent.

“Habeas corpus is not available in China,” a senior lecturer at Hong Kong University elaborated in Hong Kong’s English-language media. “With regard to what’s happening across the border, it’s something we should guard very jealously.”

In March 1996, the high court for the colonies ruled in favor of the Vietnamese. It ordered the Hong Kong government to release over 200 Vietnamese.

“It’s a victory for people in Hong Kong as much as the people detained,” lead attorney Rob Brook said of the decision.

Vietnamese protest at a Hong Kong detention camp, 1990. Online Archive of California/UC Irvine, Southeast Asian Archive

Protecting the marginalized helps everyone

Coming down so close to the July 1, 1997, handover of Hong Kong to China, the Vietnamese victory inadvertently solidified the rule of law in Hong Kong, leaving habeas corpus protections stronger than they had been before.

Today, habeas corpus and other legal rights are at the heart of Hong Kong’s ongoing protests against Chinese efforts to assert greater control over the territory. Among the pro-democracy activists arrested this year was Margaret Ng, a Hong Kong politician who more than 20 years ago wrote eloquently about the relationship between the rights of Vietnamese asylum seekers and Hong Kong’s civil liberties.

The case of the Vietnamese asylum-seekers is relevant, too, beyond Hong Kong’s current struggle with China. It demonstrates how fighting for the rights of a vulnerable minority in any country creates protections and civil liberties enjoyed by all.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand