The advent of 3D printers supposedly means we can manufacture anything in our homes. But in reality most existing home 3D printers can only make things out of certain plastics, although there are industrial systems that can print certain metals.

What has so far been out of reach is a way to 3D print high-tech composite materials such as the carbon fibre composites that are used to build lightweight but extremely strong versions of things including tennis racquets, aerodynamic bikes and even aircraft parts. But researchers from my lab at Bristol University have now developed a way to transform existing 3D printers so they can also print composite materials.

When designed properly, composites have just about the best strength for their weight of any common material, making them perfect for applications that need to be very strong but light, such as aeroplanes. Composites are usually made from very long glass or carbon fibres set in a plastic matrix. It’s the presence of the fibres, and the fact that they are all carefully arranged, that makes these materials so impressively strong yet lightweight.

Simple solution

At present, composite products are made by forming the fibres into sheets that look a bit like stiff cloth. These are then cut to shape and assembled by hand, layer-by-layer, to create the final product. As a result, composites are expensive and not easily replicated with 3D printers.

However, my colleagues and I have found a way to print composite material by making a relatively simple addition to a cheap, off-the-shelf 3D printer. The breakthrough was based on the simple idea of printing using a liquid polymer mixed with millions of tiny fibres. This makes a readily printable material that can, for example, be pushed through a tiny nozzle into the desired location. The final object can then be printed layer by layer, as with many other 3D printing processes.

Anyone for laser tennis? Tom Llewellyn-Jones, Bruce Drinkwater and Richard Trask, Author provided

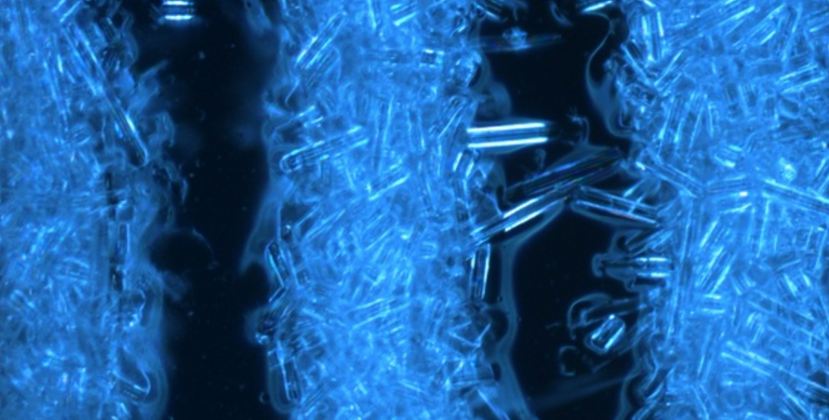

The big challenge was working out how to reassemble the tiny fibres into the carefully arranged patterns needed to generate the superior strength we expect from composites. The innovation we developed was to use ultrasonic waves to form the fibres into patterns within the polymer while it’s still in its liquid state.

The ultrasound effectively creates a patterned force field in the liquid plastic and the fibres move to and align with low pressure regions in the field called nodes. The fibres are then fixed in place using a tightly focused laser beam that cures (sets) the polymer.

Smart materials

The patterned fibres can be thought of as a reinforcement network, just like the steel reinforcing bars that are routinely placed in concrete structures such as foundations or bridges. Our study used short glass fibres in liquid epoxy polymer that are formed into longer lines of fibres and can recreate the structure of a traditional composite.

But the process has huge flexibility and can also create patterns not possible with traditional methods. By adjusting the ultrasonic wave pattern we can steer the fibres as the print progresses, producing a complex 3D architecture of fibres rather than layers of 2D structures.

One of the particularly useful features of the ultrasonic alignment process is that almost any type, size or shape of fibre can be used. This will give product designers some completely new possibilities and allow the printing of smart materials that can repair themselves or harvest electricity from the environment. For example researchers are working on embedding networks of hollow tubes filled with uncured polymer into composites. If the material is damaged and the tubes are broken open they will “bleed” polymer that will then set and “heal” the product. These tubes could be positioned in the liquid plastic with our ultrasonic printing system.

The ultrasonic technology is still in its early stages, so don’t expect to be able to buy these printers next week. But 3D printing is a very fast moving field so these ideas could well hit the market in the next few years.

Bruce Drinkwater receives funding from the UK Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).

Bruce Drinkwater receives funding from the UK Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).

Bruce Drinkwater, Professor of Ultrasonics, University of Bristol

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Jensen Huang Urges Taiwan Suppliers to Boost AI Chip Production Amid Surging Demand

Jensen Huang Urges Taiwan Suppliers to Boost AI Chip Production Amid Surging Demand  Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race

Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race  TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment

TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment  Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence

Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence  Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports

Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports  Anthropic Eyes $350 Billion Valuation as AI Funding and Share Sale Accelerate

Anthropic Eyes $350 Billion Valuation as AI Funding and Share Sale Accelerate  Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised

Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised  Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026

Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026  SpaceX Updates Starlink Privacy Policy to Allow AI Training as xAI Merger Talks and IPO Loom

SpaceX Updates Starlink Privacy Policy to Allow AI Training as xAI Merger Talks and IPO Loom  Sam Altman Reaffirms OpenAI’s Long-Term Commitment to NVIDIA Amid Chip Report

Sam Altman Reaffirms OpenAI’s Long-Term Commitment to NVIDIA Amid Chip Report  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users

Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users  Nvidia Nears $20 Billion OpenAI Investment as AI Funding Race Intensifies

Nvidia Nears $20 Billion OpenAI Investment as AI Funding Race Intensifies  Palantir Stock Jumps After Strong Q4 Earnings Beat and Upbeat 2026 Revenue Forecast

Palantir Stock Jumps After Strong Q4 Earnings Beat and Upbeat 2026 Revenue Forecast  Oracle Plans $45–$50 Billion Funding Push in 2026 to Expand Cloud and AI Infrastructure

Oracle Plans $45–$50 Billion Funding Push in 2026 to Expand Cloud and AI Infrastructure  SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers

SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers  Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate

Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate